STEM Knowledge Puts Middle Schoolers in Driver's Seat

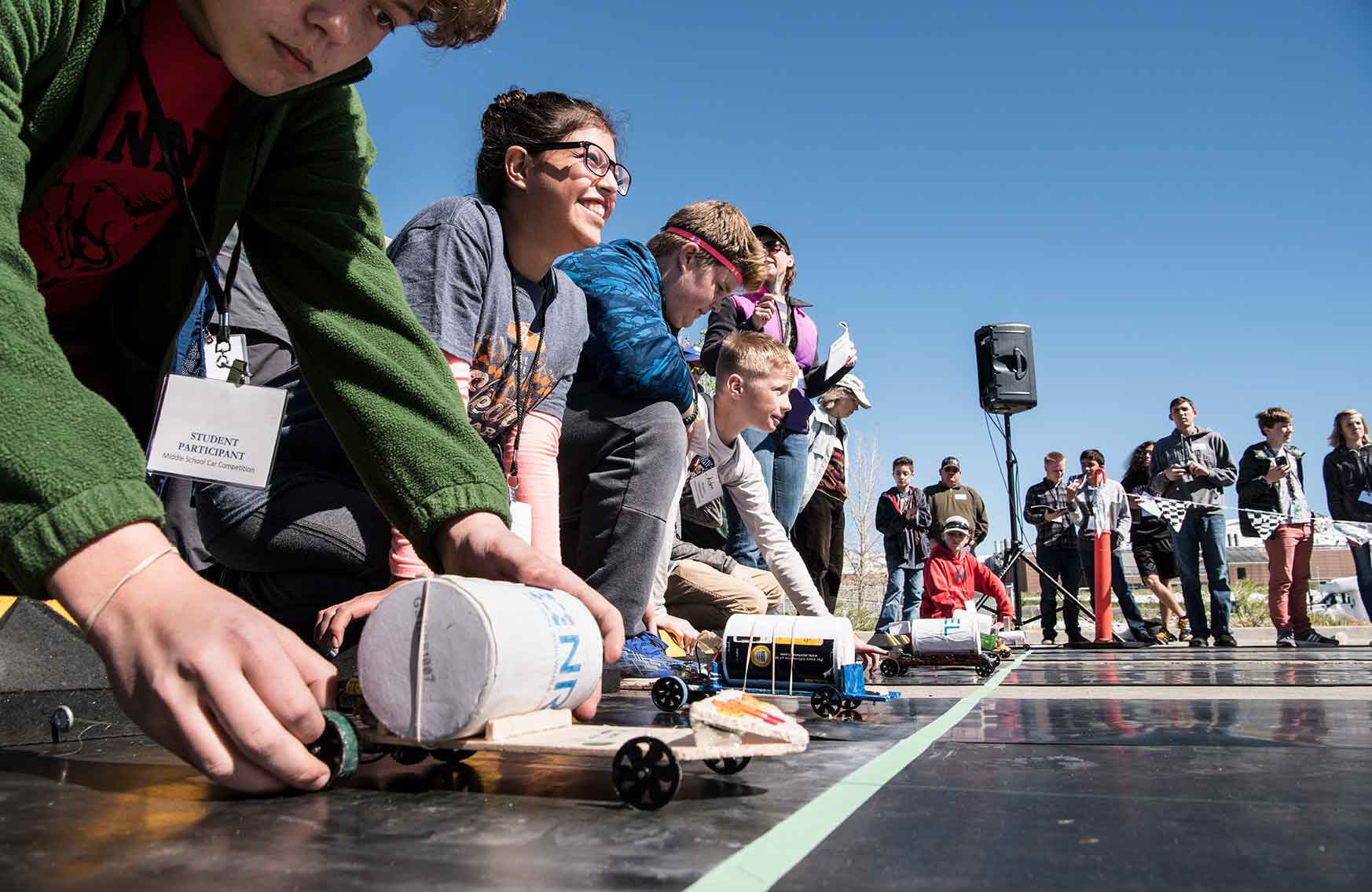

The Middle School Electric Car Competitions attracted students from 18 schools across Colorado. Photo by Dennis Schroeder

The cars raced down the straightaway, unless they didn't. Forward momentum can be a problem with solar- and battery-powered model cars designed and built by middle school students.

"There's a lot to getting these cars to actually move and go," said science and math teacher Catherine Tuell between races at the Middle School Electric Car Competitions, held on May 20 at the Energy Department's National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) campus in Golden. "There's a lot of problem solving and persistence. That's the main thing."

Tuell, who teaches at The Logan School in Denver, accompanied six of her students to the event. In all, 53 teams from 18 Colorado middle schools gathered outside under a cloudless sky for a day at the races. The cars that raced were products of teamwork, creative thinking, and an understanding of scientific principles. Although each school started with the same basic car components, there was a lot of room for innovative approaches and experimentation.

A series of time trials and double eliminations narrowed the number of competitors, leaving 16 teams in the solar and lithium-ion battery categories racing along a 20-meter neoprene rubber track for the championship. In between races, the students could run their cars on test tracks or refine their designs and gear ratios. Hot-glue guns, soldering irons, and coping saws were among the tools available for making improvements or repairs. Getting to this point, ready to face rival teams, required "a lot of planning," said Jeremy Anderson, a math teacher at Resurrection Christian Middle School in Loveland and coach to its two race teams.

"I think one of the biggest challenges was getting the kids to think outside the box and not stick with the base models and experiment—to be OK with failure," Anderson said. In preparing for the event, his students "had a lot of cars that just raced once and got broken down and were rebuilt. It took a lot of experimentation on their part."

The know-how to make a race-worthy car comes to students immersed in science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) courses. "I teach regular science, but these kids get a double-dose of science by taking a STEM elective," said Susan Coveyduck of Manning Options School in Golden. "They have two hours of science a day. They still get a broad spectrum of content in the regular science class. This is the application. This is the hands-on problem solving."

Coveyduck accompanied 16 students to the event, with the teams equally divided between the solar and battery categories. Just before the alert that signals the start of each solar race, contestants uncover their cars' solar panels. Battery-powered cars must have and on/off switch in the body design, so the teams racing those cars merely have to turn the motor on.

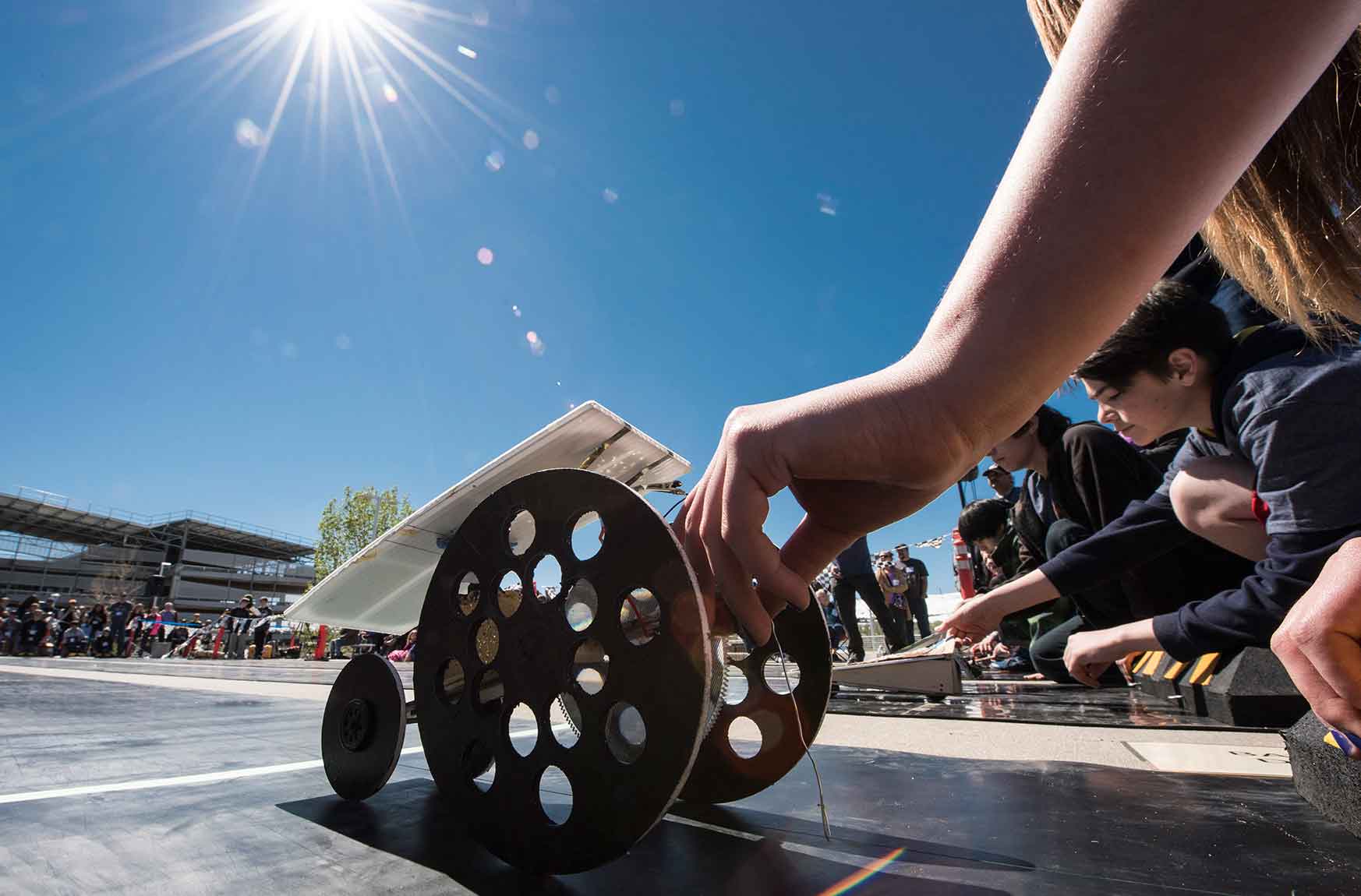

The races took place on a neoprene rubber track that was 20 meters long. Photo by Dennis Schroeder

Battle of the Batteries

Amanda Opp and her friends, all in eighth grade, raced as Manning Battery #1 after having previously built a fast-moving solar-powered car in their STEM class. For their battery-powered vehicle, they attached a small motor, axles, and wheels to a lightweight plastic paint tray. The cars in the battery competition must carry a 26-ounce cylinder of salt, so the deep well of the paint tray proved to be an ideal design element—but not one without complications.

"We have to hold a payload, that salt container, and the way we positioned it we had to figure out how to hold it where it was and not affect the wires," said Fong Lieu, another member of the Manning Battery #1 team along with Hallie Greco. Their tinkering worked. In the final race, Manning Battery #1 outperformed the other model cars and reached the finish line in 6.7 seconds. The team from Douglas County's Parker Performing Arts School was only a tenth of a second behind. Manning Battery #2 came in third at 6.9 seconds.

Parker Performing Arts, which also had a team in the solar division, was ably represented in the battery-powered race by Sara Boland and Breken Sharp. Both are fifth graders at the school, which classifies students in fifth through eighth grade as middle schoolers. Coming up with the right design "took quite a while, but not too long," Sharp said. "Finding a way to carry the salt was probably the hardest part." To solve that problem, they built a truck that could house the container and dubbed their entry Terry the Salt Truck. In addition to their award-winning time, Boland and Sharp also left with the first-place trophy for best design among the lithium-ion vehicles.

Solar Cars Burn Rubber

Sebastian Tabares and Kyle Kim, sixth-graders from Kent Denver, comprised the only team from the suburban school. They were interested in building an electric model car even before they knew about the competition. Their solar-powered car came together through trial and error.

"We had to test a bunch of gears and some of them broke or were too big for the axle," Tabares said. Kim: "Or too small." Tabares: "Yeah."

The races alternated between cars powered by solar panels and those using a lithium-ion battery. Photo by Dennis Schroeder

The resulting car incorporated half of a plastic soda bottle to tilt the solar panel and aluminum foil to better focus the sun's rays—and proved fast enough to be among the final eight cars competing. The fastest solar car, the Stargate Purple Team from Stargate School in Thornton, finished the race in 5.73 seconds, just ahead of Ken Caryl Middle School's time of 5.753 seconds. The Stargate Silver Team ended the day in third place at 5.687 seconds. The Kent Denver team finished in fourth place with a time of 6.816 seconds.

Leaving NREL with a trophy would have been nice, but Kent Denver coach (and Kyle Kim's dad) Kelly Kim had something else in mind when asked what he hoped the team would take away from the race: "That you can actually use renewable energy for practical purposes. It's not just something you read in a book," he said.

Visit NREL's Energy Education website to learn more about the ways the laboratory inspires students to explore solutions for future energy needs.