NREL Partners With Black Farmers' Collaborative To Plan Solar Panels for Florida Farms and Churches

On Cetta Barnhart's demonstration farm in Monticello, Florida, she grows citrus trees, leafy greens, and other produce that often goes to the community-supported agriculture project she founded, Seed Time Harvest Farms. Soon, there will be a new addition on her property: solar panels.

Barnhart's farm is one site where U.S. Department of Energy National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) researchers are helping the Black Farmers' Collaborative further plans to incorporate clean energy technology on farms and in communities. On top of helping Barnhart scope out plans to integrate solar panels on her farmland—a concept called agrivoltaics, in which solar panels benefit crops or livestock around them—researchers also helped the community lay the foundation for installing solar panels on houses of worship in and around Bealsville, Florida—a town about 25 miles east of Tampa. They hope the concepts will serve as models for generating solar energy throughout the state.

"I had already looked into doing solar on my property and was just looking at it to have solar as the backup," Barnhart said. "But when we started talking as a team and then we found out about the agrivoltaics portion [and] how that can be incorporated into farming, it really brought forth a bigger and better opportunity to not just benefit by having it but also sharing that with other farmers."

Agrivoltaic systems have the potential to not only increase income for farmers, she said, but also provide a chance to build wealth for future generations.

The work was a part of the Clean Energy to Communities (C2C) Expert Match program, a U.S. Department of Energy initiative that pairs communities with researchers from national laboratories to provide short-term technical assistance to address clean energy goals. Bealsville and the Black Farmers' Collaborative were among dozens of communities that applied for and received support for their energy goals through the program as of June 2023, and more communities are in the pipeline to work with researchers to address their local energy challenges.

History of Bealsville and the Black Farmers' Collaborative

Bealsville was founded by newly freed enslaved people following the Civil War, and it has remained home to Black farmers ever since. It is among Black farming communities in Florida facing climate and energy challenges that range from changing weather patterns to high energy costs to food insecurity.

Building trust with NREL before partnering with the laboratory was key to the success of this effort.

"Black farming communities—including in my own family—they're typically underserved … and there's a lot of equity and environmental justice concerns within these communities," said Dana-Marie Thomas, an NREL resilience researcher and the community lead for the laboratory's work with Bealsville. "They talked about a lack of trust in working with government organizations like NREL."

The Black Farmers' Collaborative, a group based near Bealsville that was founded by pastor and community advocate Rev. Jerry G. Nealy, spent about 18–20 months honing their energy priorities, gathering support, and forming a relationship with NREL researchers before applying for assistance through the Expert Match program. Velma Deleveaux, a member of the Black Farmers' Collaborative team, said it takes time to develop trust even when researchers enter Black communities with good intentions.

"There's so much loss that Black farmers have experienced through discrimination, so there is a lot of skepticism when people come into communities with new programs," said Deleveaux, managing partner of the business consulting firm Veaux Solutions. "Listening on everybody's part—that made it a great team, and I think that common interest on all sides is what made this work."

Deleveaux was among a diverse group of stakeholders that participated in meetings with NREL researchers throughout the Expert Match process. Alexandra Kramer, an NREL researcher who helped the Black Farmers' Collaborative develop plans for installing solar panels on houses of worship, said having perspectives from an array of invested community members—including farmers, local and state leaders, educators, and consultants—was valuable throughout the project.

"The biggest thing I learned from them is to build a coalition and bring it to the table," Kramer said. "They had buy-in from so many fantastic professionals, and they had community leaders who had deep relationships with their communities."

The NREL research team helped the Black Farmers' Collaborative narrow their focus to two solar-energy projects, create designs and plans for implementing them, and prepare to apply for funding to build the systems.

"It's collaborative," said James McCall, an NREL researcher who worked on the community's agrivoltaics design and analyses. "We're not going to go off and get you an answer; we really want to work with you."

Incorporating Agrivoltaics on Farms: "A Game-Changer"

Incorporating solar panels on Barnhart's farm was one of two priorities the team chose for their Expert Match project.

"You have to think strategically about building momentum and credibility along the way," Deleveaux said. "You could roll out a really great design with a farmer that nobody knows about or trusts. But we chose a demo farm, right? And it just happens to be run by a woman who is just great, respected, and known in the community."

Barnhart founded Seed Time Harvest Farms in 2012 to connect farmers to local consumers, and her 14.5-acre farm serves as a demonstration farm and part of the community-supported agriculture group. She teamed up with Nealy and the Black Farmers' Collaborative to support Nealy's vision for helping Black farmers care for their land in Florida and beyond.

"That's the real gist of what this team is looking for: How can we bring change into our community that's long-lasting, that's impactful, and that helps the Black farmers?" Barnhart said. "This opportunity we believe with solar is a big one—changing the energy game."

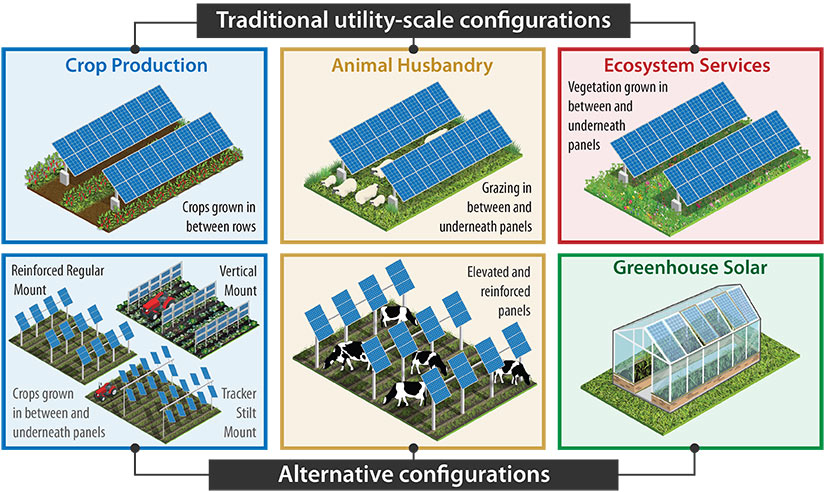

NREL agrivoltaics researchers worked with Barnhart and the collaborative to design six options for agrivoltaics systems that could integrate with different crops on one acre of her farm, starting with string beans. The team also provided modeling to understand the balance between installation costs, energy output, and crop production.

"There's no one-size-fits-all solution," McCall said. "It's really about providing this landscape and then allowing the community to say, 'This is what I want to do.'"

The Black Farmers' Collaborative hopes Barnhart's agrivoltaics becomes a model for other farmers who want to implement solar energy systems.

"It was a game-changer when we really started looking at how incorporating agrivoltaics into farming could play into families," Barnhart said. "The project has helped me develop that conversation and come up with a real plan of implementation that can be duplicated."

How Black Churches Can Help Lead the Energy Transition

In addition to planning agrivoltaics for Barnhart's farm, NREL researchers developed a guide for installing solar panels on houses of worship and other commercial-scale buildings in Florida. The "road map" includes guidance for determining which type of solar to install (such as rooftop solar panels, ground-mounted solar, or community solar panels); assessing buildings' readiness for solar panels; understanding regulations that affect solar installation; securing solar contractors; maintaining the solar system; and decommissioning solar panels. The researchers also identified funding options Bealsville could pursue to complete the work.

"Outlining the process all the way through was one way NREL could provide valuable insight that would allow the community to make their own decisions," Kramer said.

Bealsville has identified several houses of worship in the region that could be suited for solar panels. Nealy said it is an opportunity for Black churches to show their communities the advantages of solar energy.

"It has been the faith-based community, the Black Church, that has given leadership to our community," Nealy said. "We can help spread that this will be a great benefit to our community and be a good green corporate citizen."

How Solar Energy Could Provide "A Rippling Effect" in Bealsville

Nealy hopes the solar industry creates job opportunities in and around Bealsville. The community is looking to partner with correctional facilities to train formerly incarcerated people to build, install, and maintain solar panels, he said.

"All of these projects, we're expecting them to do more than what the focus is," said Charis Consulting Group President and CEO Saundra Johnson Austin, a member of the Black Farmers' Collaborative. "We're expecting them to have legs—a rippling effect."

Johnson Austin said she hopes the project "inspires a generation of STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math] professionals," a goal shared by Perry Blackmon III, a community activist, sustainable cattle farmer, and member of the Black Farmers' Collaborative in Selma, Alabama. Blackmon, a wellness coach at Selma High School, said he does not see enough enticing jobs to keep young people in Selma.

But models like Barnhart's farm could provide a destination for K–12 students to learn about solar energy. Blackmon hopes the solar industry offers youth in his community an alternative to some of the more common careers available to them now.

"Solar and renewable energy can give these kids a purpose to want to do something different," Blackmon said. "Because everybody doesn't want to be a cosmetologist, a nurse, a welder, or a brick mason."

These types of renewable energy projects have the potential to uplift communities and bring lasting change, Barnhart said.

"You run into these challenges with most governmental programs that only repeat cycles and don't really bring people out of cycles. And I think what we're working on here is to bring people out of cycles and to new opportunities," she said. "I'm just grateful to be a part of that type of program where we can hopefully see some changes."

Learn How Expert Match Can Support Your Community

Although NREL provided the road maps for the Black Farmers' Collaborative to embark on solar projects, the Black Farmers' Collaborative—like other Expert Match communities—guided the decision-making.

"It's very important that the community implements these projects on their own terms and that they are owners of their projects," Kramer said. "It's not our place to have decisions about that land."

Jordan Macknick, an NREL researcher who led the agrivoltaics portion of the project with McCall and Brittany Staie, said the group was a great fit for Expert Match because they were prepared, enthusiastic, and open.

"The stakeholders have a lot of ideas, they have a great cohesiveness among them, and they knew they wanted to do something bold. They knew they wanted to do something that would have a broader impact," Macknick said. "They had the drive, and they just needed a little bit of help … to bring it to fruition."

C2C connects community-based groups, local governments, utilities, and other organizations with national laboratory experts to close the gaps between communities' clean energy ambitions and real-world deployment. The technical assistance offered through C2C can offer meaningful insights around clean energy decision-making to help communities achieve resilient clean energy systems that embody local and regional priorities. For example, C2C analysis can provide insights on the financial and social costs and benefits of electric vehicles, geothermal systems, or capturing and storing solar energy. Such analysis provides community-specific information on the funding and support needed to bring clean energy projects to fruition.

Expert Match is one branch of the C2C program that offers 40–60 hours of technical assistance to communities over the course of 2–3 months and reviews applications on a rolling basis. Learn more about the C2C Expert Match program and find out how to apply.