From Instant Grits to Polymers: Scientist Kat Knauer Is Laser Focused on Plastics Pollution

Polymer Scientist Applies Scientific Method To Solve Greatest Environmental Challenges While Making Lives Better

Kat Knauer enjoyed science classes as a young girl but her understanding that science could be used as an instrument for good was solidified when a beloved family member grew ill.

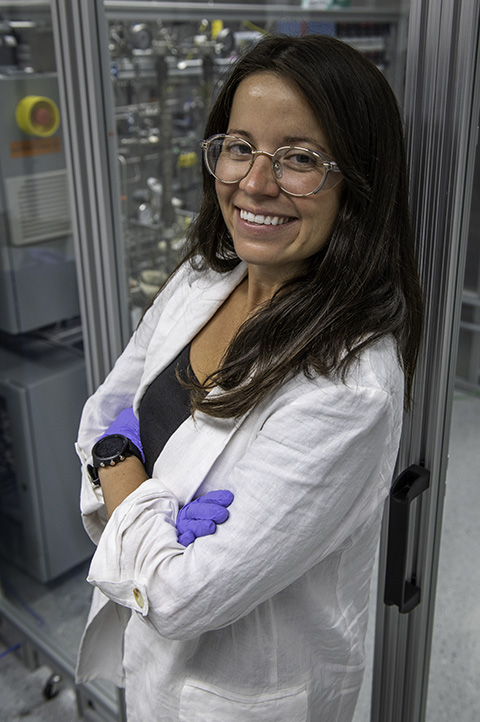

Kat Knauer is ready to take on the global plastics pollution problem. Photo by Bryan Bechtold, NREL

Her childhood dog, Penny, was having a severe reaction to the pesticides her mother applied to fire ant mounds dotting the landscape around their south Florida home. Knauer became concerned for Penny’s health and turned to the scientific method for potential solutions.

For her science fair project that year, she chose to screen and test environmentally friendly methods for fire ant extermination. The most effective method for dispatching fire ants to the afterlife? That ubiquitous southern staple, instant grits. She discovered, among other things, that the tiny ant bodies could not handle the high sodium content or rapid expansion of powdered instant grits.

She ended up winning the science fair. Then she won the state science fair. Knauer grew surprised and then intrigued that her friends, family, teachers, and community were excited about the science results.

The impact surrounding her experiment provided the young Knauer with an impression that science could solve our toughest environmental problems while making people’s (and pets') lives better.

Today, Knauer is still driven to unveil scientific solutions to solve challenges for not only her loved ones but also the whole world itself. As a polymer scientist and the chief technology officer of the NREL-led Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment (BOTTLE™) consortium, Knauer is responsible for helping solve one of the world’s greatest challenges—plastic pollution.

BOTTLE is a multiorganization consortium supported by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Bioenergy Technologies Office and Advanced Materials and Manufacturing Technologies Office. The consortium is focused on developing new chemical upcycling strategies for today’s plastics and redesigning tomorrow’s plastics to be recyclable by design.

In the interview below (edited for length and clarity), Knauer discussed the evolution of her career and how NREL, the BOTTLE team, and its committed partners are passionate about discovering science-based solutions to our plastics waste problem.

Tell me what led you to be a polymer scientist focused on our plastics problem?

My success at the science fair was certainly an influence, and as I grew older it became clear that I really enjoyed math and chemistry. When it came time for university, I chose chemical engineering because it seemed like this perfect combination of calculus and chemistry.

I was always passionate about environmentalism. While at Florida State University I was fortunate to do polymer research at a new campus institute focused on materials science. There I learned that polymers were the primary components of plastics.

I also came to realize that we had this big plastic waste problem polluting the planet, and polymers were the root cause of it. Yet polymers and polymer chemistry have made the world a better place and have improved the quality of life for most of society in many ways. But polymers aren’t bad. It’s just that we’ve abused them.

We have responsibilities as scientists to find a solution for plastic waste mitigation, and I felt like if I received a Ph.D. in polymer chemistry, people would listen to me and think I was an expert, all of which would help me make a bigger impact on our plastics problem.

After your Ph.D. you worked for the private sector. How did those experiences impact your career?

My thoughts were that if I worked for a large plastics and polymer science corporation, I could start making an impact right away by helping commercialize plastic waste mitigation technologies faster than staying in academia. I started working on recycling technologies and learned how recycling can become commercially and economically viable. However, I discovered quickly that large corporations can be slow and risk averse with barriers to innovation. I needed to move faster.

I made the leap to a startup company, called Novoloop, run by this amazing group of women and helped develop a chemical recycling pathway for hard-to-recycle film waste, like grocery bags and pallet shrink wrap. The pathway we developed oxidized that film waste down to valuable building blocks to make new polymer materials. And this polymer—a thermoplastic polyurethane or TPU—that I worked on for many years has reached commercial viability as the sole of a running shoe.

That’s nice to see all that hard work turn into a sustainable, commercial product.

Yes, the coolest part is that we were taking something that's considered single use and so low value like a grocery bag and making it into a material that's now going into $200 running shoes. This is upcycling at its finest.

Kat Knauer holds the first prototype of the TPU polymer developed from hard-to-recycle film waste like plastic grocery bags. The final polymer was upcycled in the sole of running shoes (pictured right). Photos from Novoloop

So, your transition from the private to public sector was finalized by earning the chief technology officer (CTO) role for BOTTLE, which has a nice ring to it.

Yes, definitely.

What made NREL and BOTTLE seem like a good fit?

I loved my time at Novoloop. It’s where I truly became a better chemist. I also experienced the pivotal process of commercialization by taking an idea from bench scale to a real product. Yet, after experiencing the production of recycled TPU for a running shoe, I realized I wanted to work on a multitude of technologies and make a bigger dent in as many ways possible. I wanted to research the entire plastics waste stream and supply chain.

While at Novoloop, I attended the National Academies’ Chemical Sciences Roundtable where they invited scientists to talk about the plastic waste problem. Gregg Beckham, senior research fellow at NREL, spoke at the roundtable and laid out his vision for a new plastics upcycling consortium, what would become BOTTLE. I was excited about the potential. This was what I wanted to do.

Gregg and I spoke, and he encouraged me to do a seminar at NREL. I did, and when I was here, I knew this is where I wanted to be. The people here, the caliber of work that was going on, and Gregg's vision for BOTTLE were aligned with my mission and goals as a scientist.

Over the next two years, BOTTLE became real. That’s when Gregg reached back out to me, and we started talking about how I could become involved. Our conversations evolved into the CTO role.

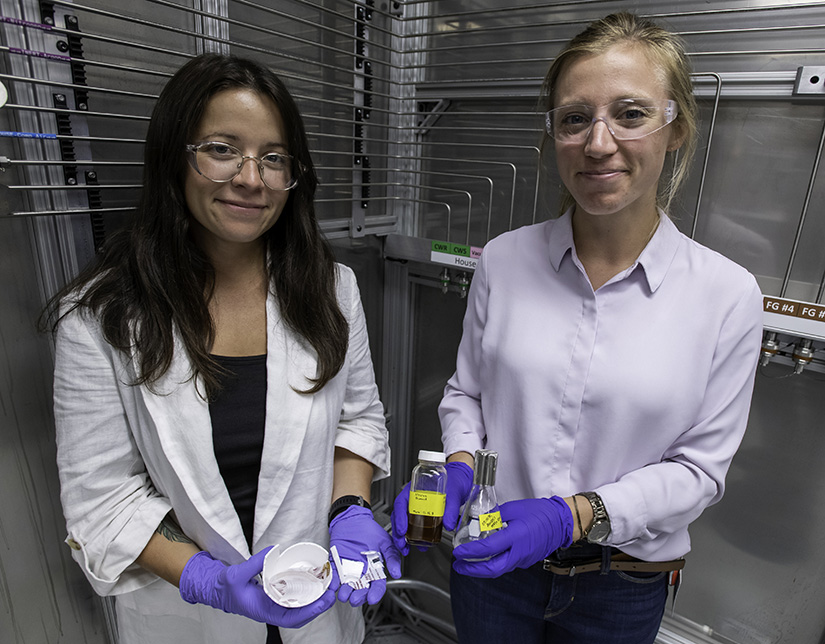

Kat Knauer and Allison Werner are studying how the Pseudomonas putida bacterial strain, engineered at NREL, will perform at breaking down a variety of oxidized plastics in microgravity conditions on the International Space Station. Photo by Bryan Bechtold, NREL

It seems like everything aligned well between yourself and NREL. What are your core responsibilities as BOTTLE CTO?

This is a unique role in that it’s a hybrid—I'm half business development (BD) and half researcher. I manage strategic external partnerships by developing, defining, and leading specific research projects with these partner companies. For the BD part, I show U.S. and global companies how BOTTLE technologies can meet their sustainability or plastics circularity needs. I also define with them what a project at NREL would look like and the outputs we could realistically deliver to them.

For the researcher part, once we have a project agreement, I then pull a team together and start executing and working on that technology for the client.

My research falls in higher technology readiness level (TRL) ranges. Everything I do with BOTTLE looks at DOE-funded technologies with a TRL of maybe 3. I take these to strategic partners and say, with this much money we could get you up to TRL 6, pre-pilot level, and we can help you deploy and commercialize.

We have a diverse portfolio of industrial partnerships, all different types of projects with some hitting the deployment phase. We’re also spinning off startup companies. We are incredibly focused on making these plastic technologies a part of the U.S. economy as quickly as possible.

Speaking of those partnerships, I’ve heard that you’re an amazing recruiter of BOTTLE industry partners. Can you share with us any secret sauce for your success?

It's not something scientists always love to hear, but you do have to be personable to get these companies to want to talk to you. In addition, I have the backing of NREL and all the great technologies and reputation that comes with this organization. But I also think a big part of this is that I'm brutally transparent and honest with these companies. I'm very realistic with them and upfront with what's possible. I also talk about costs right away so that they're not shocked and surprised later. I think companies appreciate this transparency.

Also, the model we've adopted in BOTTLE, which I alluded to before, is that after executing that agreement, I don’t disappear. I remain their point person. I lead the project and I mentor the researchers and the postdocs, and I write the papers and I make the presentations. I think a consistent line of communication with the person that built up this trust with them is something they've really come to value. And I really appreciate it.

BOTTLE has been up and running for a bit. What are some big challenges you’ve overcome?

At BOTTLE we have two challenges happening in tandem. One is how to recycle today's waste as efficiently as possible with the highest economic benefit and the lowest environmental footprint. The other is how to rethink waste because the plastics used today were never designed to fall apart. This is redesigning and making new materials for the future that are more inherently recyclable by design, biocompatible, biobased, and potentially biodegradable.

At first, we pitched companies on how they could redesign their material and packaging in a sustainable way. The companies weren’t receptive. They were interested in just recycling their plastic trash today. I do think that the true solution is turning it off at the tap through redesign rather than just keep making as much as we're doing now the same exact way and hoping a market evolves to recycle it.

Kat Knauer (left), gives a brief presentation on plastics research for Vanessa Z. Chan (right), chief commercialization officer and director for the Office of Technology Transitions of the U.S. Department of Energy, during Chan’s visit to NREL. Photo by Werner Slocum, NREL

So how did you convince these companies to work on redesigning their plastics?

When we discovered that we could redesign these products at cost or slightly above, that’s when it shifted, and more companies started listening. Our first big win we had was with The North Face, who is funding a project to replace the current polyester fiber used in their apparel gear with a biobased polyester that will be just as robust but has a biodegradation pathway.

And that's not because we want clothing to biodegrade. Around 46% of microplastics in the environment come from plastic fibers that are shed during clothes washing. Instead of figuring out how to stop all shedding because people aren't going to stop washing their clothes, we pitched the company on redesigning their material to be natural, biocompatible, and not persist in the environment for 400 years.

OK, one last question. If you were queen for a day and had unlimited power to make one change in the world, what would it be?

There are these little plastic packages that hold a small serving of mustard or ketchup for example. These sachet packets are the most over engineered materials in the world with something like eight different layers of completely different types of polymers or metals and are unrecyclable. In places like Indonesia and the Philippines these little sachets make up nearly 50% of their waste streams. So, I would make a recycling economy infrastructure for these sachet packets based on material that is recyclable and highly desired.

Learn more about NREL’s bioenergy research and BOTTLE solutions to mitigate plastic waste pollution.

Last Updated May 28, 2025