Beneath the Surface: The 'Spark Squad' Behind the Spark Squad

How Cartoon Joules Are Capturing Hearts and Minds of Tomorrow’s Clean Energy Workforce

If you are a 1990s kid, you probably remember the punny Captain Planet with his teal mullet, antipollution tirades, and Earth-saving Planeteers. The cartoon was surprisingly successful, despite its didactic speeches and morose pandas. But now, as several of the show’s dire climate storylines—like a flood-prone, food-scarce future—are seeping into reality, the super crew is long gone.

Gone, but not forgotten.

Captain Planet (plus turtles, flopping fish, and a chemist dad) inspired three now fully grown millennials to invent a super squad for a new generation. The Spark Squad Comic Book series features three not-so-super-powered, but just as powerful, kiddos named Jasmine, Aria, and Thomas. The series first came out in 2022 and was developed by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the U.S. Department of Energy’s Water Power Technologies Office.

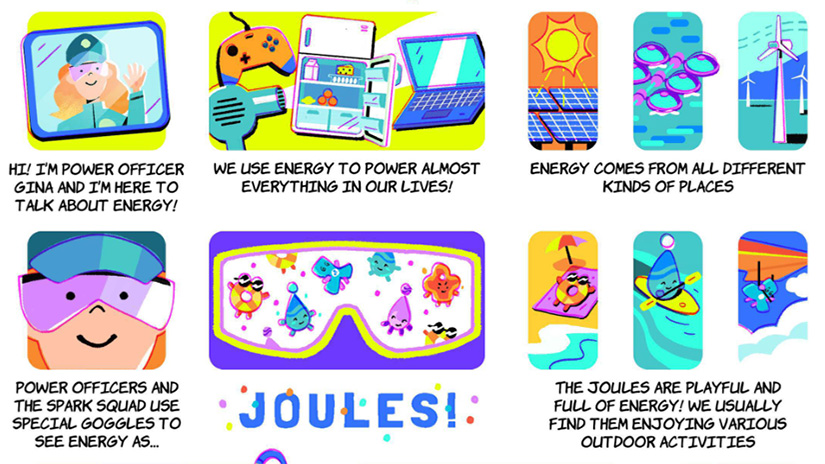

Just like their creators, Heidi Tinnesand, Dale “Scott” Jenne, and Jenny Wiegele, these young Electriciteers are more practical than their predecessors. Instead of using five magic rings to call up a superhero, Jasmine, Aria, and Thomas capture joules (units of energy) to save themselves—and the world—one clean energy invention at a time.

“We liked this ‘everyday superhero’ vision of kids,” said Tinnesand, a mechanical engineer at NREL and the first spark to ignite the Spark Squad. “Superheroes don’t have to wear capes.”

Like their everyday superheroes, the "spark squad" behind the Spark Squad are a practical trio. They did not launch their comic series just to turn their day jobs into cartoon adventures; they had a bigger goal in mind. Today, too few kids are choosing to pursue clean energy careers. As the world ramps up production of clean energy technologies, like wind turbines, wave energy devices, and solar panels, the clean energy industry will need to grow a larger and more diverse workforce than we have today—to build an army of employees, as the World Economic Forum notes.

Without that army, we cannot properly fight climate change. And there is no army without Electriciteers.

“We’re not reaching people fast enough,” said Wiegele, a research project manager in Hydropower and Water Systems Deployment at NREL, who helped launch the Spark Squad series. Most kids start to chase fascinations when they are 10 years old or younger, she said. Wiegele, for example, was terrified of killing turtles. Even though she grew up in Wisconsin—far from any ocean—she remembers cutting up the plastic rings that bind soda six-packs, which still strangle sea creatures today. That initial fear drove Wiegele to choose a job where she could protect wildlife and the environment.

Jenne, a Captain Planet kid, was always tinkering with bikes and cars (a pastime that only strengthened into adulthood when he built a wave energy device in his garage). But, like Wiegele, fear pushed him into a career in renewable energy. He still remembers watching TV and seeing a clip of a kid who left the water on while he was brushing his teeth. The tap drained a nearby lake, leaving a fish flopping and gasping in mud. “It was really morbid, but it stuck with me,” Jenne said.

Tinnesand’s motivation to save the planet was a little less morbid. “It was definitely my dad,” she said. Tinnesand’s dad was a chemist and high school chemistry teacher. “He knew so much about the world and inspired me to do the same,” she said. “He helped me learn things.”

None of the three mentioned pretty graphs, compelling statistics, or peer-reviewed papers in their scientific origin stories. “The reality of it is that doesn’t work well,” Jenne said. “It’s not the best method to reach beyond the scientific community. And it doesn’t get people excited about new things.”

Journal articles, white papers, and technical reports might inspire fellow scientists, but these jargon-filled rundowns are unlikely to inspire kids. But visuals and stories have that power—in fact, in 2018, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences held a panel to discuss how art can bridge the gap between “white-coated gurus on the mountaintop” and the rest of the world. Scientists have also found that art can be a more effective way to talk about climate change.

Tinnesand, Jenne, and Wiegele created the Spark Squad for this exact reason: to bridge the gulf between renewable energy experts (like themselves) and the next generation. In the first comic book, the kiddo trio navigate a shrimping boat through a storm using a device that captures the power of ocean waves. They scramble to fix a lighthouse to guide that boat home. And, in the second edition, they don hard hats to hike deep inside a hydropower plant.

But even the Spark Squad creators were surprised that it was not the story or the charming characters that most captivated their young audience; the kids were obsessed with the joules. In the comics, each type of renewable power is personified by a different plump, smiley joule. Bright yellow and orange solar joules wear sunglasses and bask in the sun; wind joules fly in the breeze, while wave joules surf.

In the second comic, the Spark Squad kids capture a “Georgian Hydrojoule,” the first joule to get an official name—but maybe not the last. During a focus group with real-life kids who read the series, one reader asked for a “Geothermal Geoffrey.”

“They got stuck on the joules for like 45 minutes,” Wiegele said. The kids wanted to know: What happens to the joules after they’re captured? Do they disappear? Do joules get tired? “They were so excited,” Wiegele said. “It was awesome to see.”

That excitement is spreading—fast. So far, the series has been downloaded over 20,000 times. Even accounting for hungry internet bots, that number would still far exceed even the most highly downloaded journals. “If the definition of outreach is to reach out, this is as good as it gets,” Jenne said.

Tinnesand said she hopes the Spark Squad success demonstrates the value of merging art and science. “The kids had so many ideas for what they wanted to power,” Tinnesand said. They understand that electricity powers their video games and computers. “But a lot of these kids get lost in middle school,” she continued. “I wanted to do something to excite and inspire different kinds of students to come be part of this incredible industry.”

Wiegele agreed: “Maybe 20 years from now, they’ll say, ‘The Spark Squad inspired me.’”

Discover all the ways NREL’s experts are inspiring the next generation of clean energy champions to save the planet. And subscribe to the NREL water power newsletter, The Current, for the latest news on NREL's water power research.

Last Updated May 28, 2025