This Bat Appreciation Day, NREL Shines Light (Literally) on Bat Interactions With Wind Energy

Bat Appreciation Day is April 17, and as we pause to admire these unique creatures, we also recognize that bats face many threats, including increased deployment of wind energy. However, with support from the U.S. Department of Energy's Wind Energy Technologies Office, researchers at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) are working hard to create solutions that protect bats and other wildlife while ensuring sustainable deployment of wind energy.

The wind energy industry started to recognize bats as an area of concern in the mid-2000s, around the same time NREL researcher Cris Hein was finishing his doctorate degree in forestry and natural resources. Hein had been studying bat behavior and ecology for 10 years when he landed a job with Bat Conservation International collecting preconstruction bat acoustic data at two wind farms in Pennsylvania.

“We were just starting to see wind energy’s impact on bats at that point, so the state of the science was limited,” Hein said. “We had some concerning data from a few wind energy sites in West Virginia and Pennsylvania, but it wasn’t clear yet if the impact was isolated to the region.”

As Hein and other researchers learned in the coming years, wind energy projects were impacting some bat and bird species throughout the United States and around the world.

This began Hein’s journey down a career path focused on monitoring and minimizing wildlife interactions with wind turbines. It also led him to his current roles as program coordinator for the Bats and Wind Energy Cooperative and senior project leader for NREL’s wind energy Environmental Science Portfolio.

“After nearly two decades of research, we have developed strategies for measuring wind energy impacts, observing bat behavior around wind turbines, and minimizing collision events,” Hein said.

A special issue of the journal Animals explores several of these strategies. Co-edited by Hein and Dr. Amanda Hale from Texas Christian University, the special issue focuses on advancements in methods used to assess bat populations, tools for studying bat activity and behavior, and insights into which stimuli attract bats to wind turbines and which deter them.

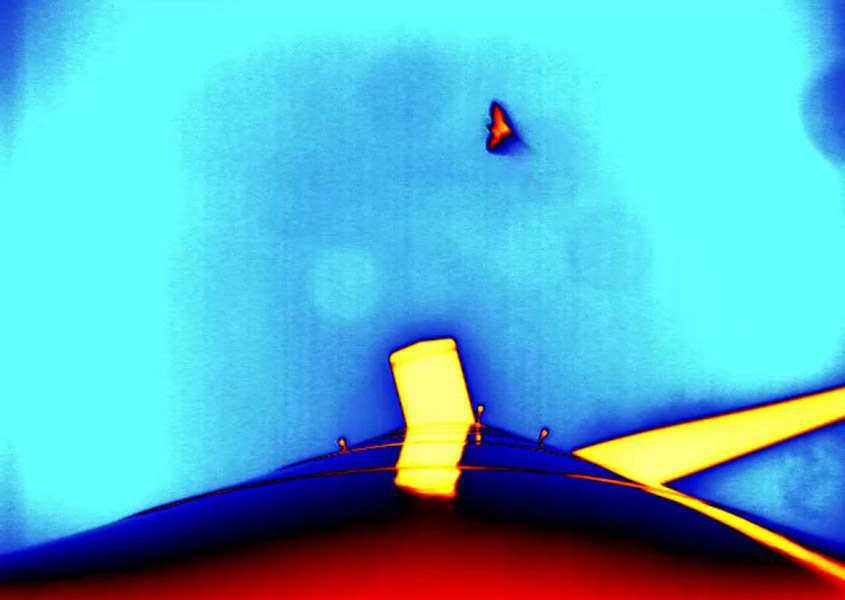

Understanding how bats behave around wind turbines is key to reducing wind energy’s impact on bat populations. Monitoring technologies like thermal imaging cameras can provide useful insights into how and when bats approach wind turbines.

“One important thing we’ve learned about bats in the last 15 years is that some bat species—particularly tree-roosting species that don’t hibernate in winter—seem to be attracted to wind turbines,” Hein said. “A possible explanation for this is that, while bats can see pretty well in the dark, they may mistake wind turbines for trees.”

This notion inspired a team of researchers led by the U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Hawaii to investigate the use of dim, flickering ultraviolet light to reduce bat interactions. The team equipped wind turbines at NREL’s Flatirons Campus with the lights and used thermal-imaging cameras to track bats’ activity around the illuminated turbines.

The idea was to make the turbines easier for bats to see from a distance to give the bats a chance to recognize that the turbines were not a good place to roost.

The results of the study, which are included in the special issue of Animals, were inconclusive. Bats still approached the illuminated turbines.

“Sometimes results don’t match the hypothesis, but that’s why we conduct these types of studies,” Hein said. But the research still demonstrated that thermal cameras are a valuable tool for monitoring bat behavior near wind turbines and for validating emerging technologies intended to keep bats and birds away from turbines.

Did You Know?

A common belief about bats is that they are blind, but the truth is bats use all their senses, including their sight, in amazing ways. Bat vision is not as sharp as that of humans and birds, but they can see well in dim light that appears dark to humans. To supplement their vision, bats use echolocation, meaning they emit high-frequency sounds and listen to the echoes that bounce off their surroundings to help them locate and identify objects around them. This adaptation helps bats quickly navigate their surroundings in the dark.

A Flight Path to the Future

Going forward, researchers need to account for the dynamic lives of bats. In a review of the existing hypotheses regarding bats’ attraction to wind turbines, Hein and co-authors recommend that future studies should investigate several social behaviors, like mating or territorial marking, as potential reasons bats approach and interact with wind turbines.

Monitoring bats’ genetic diversity and populations by collecting acoustic and genetic data can also help answer questions about how to make wind energy more environmentally friendly, according to another publication Hein co-authored.

Understanding the relationship between bats and wind energy has come a long way since Hein first began collecting bat acoustic data at wind sites, but there is still much to learn about Earth’s only flying mammal.

“As small, elusive animals who stay hidden in trees or caves during the day and only come out at night, bats are notoriously difficult to study,” Hein said. “However, by better understanding their movements, population sizes, and behavior, we can develop the best strategies for producing clean renewable energy while minimizing wind energy’s impact on bats.”

To learn more about NREL’s research on wind energy and wildlife, visit the ECO Wind: Enabling Coexistence Options for Wind Energy and Wildlife web page.

Last Updated Jan. 22, 2026