Q&A With Parthiv Kurup: A Practical Captain To Helm the Clean Energy Transition

Manufacturing Mastermind Series

Growing up in India, Parthiv Kurup saw regular blackouts. Some lasted hours; others darkened everything for days. “Those were the known blackouts,” Kurup said, which were scheduled to protect a rickety grid back in the 1980s. “Unknown, unscheduled outages happened almost weekly.”

Those dark spells sparked an epiphany for Kurup. Ever practical, he decided to join the energy sector—and change it. Though he started in natural gas, he switched to renewables when he realized their future economic value would surpass fossil fuels. Now, as a cost and systems analyst at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), Kurup studies the economic viability of renewable technologies. “For somebody to buy it, it has to make sense,” he said.

But before someone buys it—wind turbines, solar panels, or concentrating solar power (which uses mirrors to create energy in the form of heat)—someone must manufacture their materials. And those manufacturing processes come with their own energy demands and costs; Kurup helps with that, too. His analyses are streamlining manufacturing processes to reduce the sector’s energy consumption while reducing costs.

A rare combination of idealist and realist, Kurup is arguably an ideal captain for a clean energy transition. Working in collaboration with a broader team of NREL researchers, as well as those from other national laboratories, his analyses will not only help guide renewable energy solutions from manufacturing to installation; they will ensure somebody—whole industries or whole countries—understand their value.

In a recent interview, Kurup, who joined NREL seven years ago, shared how he went from blackouts to company founder to expert in clean energy technology and manufacturing.

The blackouts you witnessed growing up in India were a powerful motivator to join the energy industry. But there were other ways you could have tried to change the energy sector. Why did you choose to become a mechanical engineer?

I was always good at mathematics, physics, economics, and development. Combined, it made a lot of sense to do mechanical engineering, which led me to the power sector. My first main job was as a gas turbine engineer for a large European power utility.

Parthiv Kurup (seen here in a navy shirt and pointing at the sky) witnessing the 2018 solar eclipse with colleagues at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. Image from Parthiv Kurup, NREL

But you did not stay in natural gas. Why?

Even at that point, I had a fascination with renewable energy because I could see it was going to become very valuable in the future. Coal and natural gas have been incredibly important to create our civilization, but with climate change, renewables make much more economic and environmental sense since they don’t emit carbon. Also, what if your fuel was free? Even though the solar and wind energy technology have associated costs, the fuel—the sun or the wind—are free to harness. To me, that's a phenomenal way of saying how valuable renewable energy can be.

Did you have any doubts about switching from natural gas to renewables?

Well, my mother did. She was a successful financial consultant. When I was in my first big job after university, she would jokingly say, ‘When are you actually going to make real money?’ I said, ‘You know what? I know one day the value of what I'm doing will be seen, so I'm willing to earn the skills.’ Once I came to the United States, it was clear. She understood why I was willing to take on technically challenging engineering jobs to gain the exposure and experiences to be able to then jump a significant step.

But before you came to the United States, you started your own renewable energy consulting company in London, right?

Correct. It was a renewable energy consulting company that was aiming to help bring concentrating solar power (or CSP) into the Indian market by working with a CSP technology and project developer. That was going well, but eventually, it became clear that my level of impact would be greater at an organization outside my own. Then, NREL reached out and said, ‘There might be something of interest for you here.’ I was like, ‘Wow. What a phenomenal opportunity.’ I was willing to dissolve my company to come here.

So, what does your mother think about what you're doing now? Is she proud?

Yes. She’s very proud. In fact, she’s now running a company that’s bringing solar power to Nigeria. She said she used me as the inspiration for that.

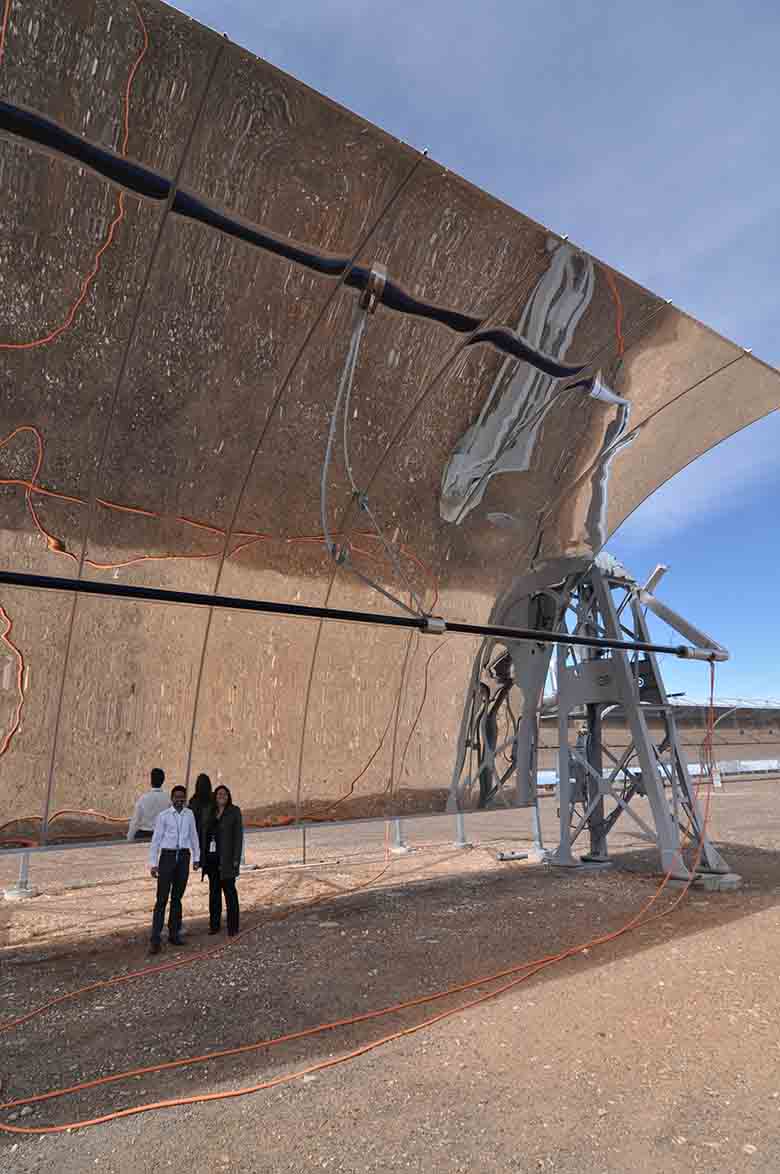

Parthiv Kurup (in white) and colleague Judy Netter stand beneath one of the huge mirror-like parabolas used to generate solar thermal energy during a visit to the Colorado-based concentrating solar power developer SkyFuel’s test site. Image from Parthiv Kurup, NREL

You were originally enticed to join NREL to work on evaluating the economic viability of CSP. What did you learn by studying this market?

One of the big things I saw was that the market for CSP electricity had been slowing down. CSP tried to go for these massive, very capital-intensive projects, which meant the likelihood of deploying these was low relative to solar photovoltaics.

So, if these projects were not working, how do you convince developers to try something new—to generate thermal energy instead of electricity?

I work with developers, so NREL can say to the Department of Energy, ‘These are the issues, and these are the potential levers needed to change them.’ For example, we just studied how competitive new thermal technologies might be against, say, a natural gas system at a specific site. We were able to show through the economics and analysis that if the cost of the technology doesn't get to a specific level, it wouldn’t be competitive unless you subsidized it, like with carbon credits or incentives. That type of analysis can help drive R&D decisions.

What does that mean for technology developers?

I'm a very practical person. I work with great researchers who think about developing new ideas and technologies, and I'm like, ‘That's great, but why should the developers and end-users go through the pain to change what they're doing today?’ My strength is in evaluating technology changes to improve decisions. For example, what issues need to be considered before you start spending the money and doing the technical research? Before you start manufacturing? Analysis can save millions later by spending hundreds of thousands early.

Especially in manufacturing, right?

Right. I was recently involved in a project called ShAPE, which stands for Shear Assisted Processing and Extrusion. Working with the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, who led the project, we provided detailed analyses of ShAPE to better understand the cost and energy reduction potential of ShAPE manufacturing. The technology could radically change manufacturing processes to produce better materials with enhanced properties while using significantly less energy and emitting far less carbon. It takes less time, too. So, we’re maximizing efficiency and minimizing waste for products used in transportation, aerospace, defense, and marine applications, resulting in 75% reduction in carbon emissions and even all the way up to 90%.

So, you are like a bridge between the technological innovators and the practical market.

Correct. For example, we have huge mandates today, like a 100% clean energy grid by 2035. This is great, but there are real issues preventing such an expansion of renewable energy technologies from happening. For example, the U.S. currently has less than 50 megawatts of offshore wind capacity installed, but there could be hundreds of gigawatts of offshore wind potential. This huge expansion will face significant challenges, including domestic manufacturing capacity.

Speaking of global changes, does it feel like you can have a big impact working at NREL?

Yes, it does. I'm also realistic that these massive national goals, like a zero-carbon grid by 2035, take a huge amount of time and effort. I'm fortunate to work with phenomenal people who really want to change the world.

What advice would you give to a young scientist considering a career in renewables?

As Wayne Gretzky put it: ‘Skate where the puck is going, not where the puck has been.’ Renewable energy is where the puck is going. But it’s not the only way to make an impact in the world. If you're trading your genuine life force for something—whatever it is—it should be for something that has resonance and value to you.

Interested in building a clean energy future? Read other Q&As from NREL researchers in Advanced Manufacturing, and browse open positions to see what it is like to work at NREL.

Last Updated Jan. 22, 2026