How NREL Is Fanning the Sparks of Innovation

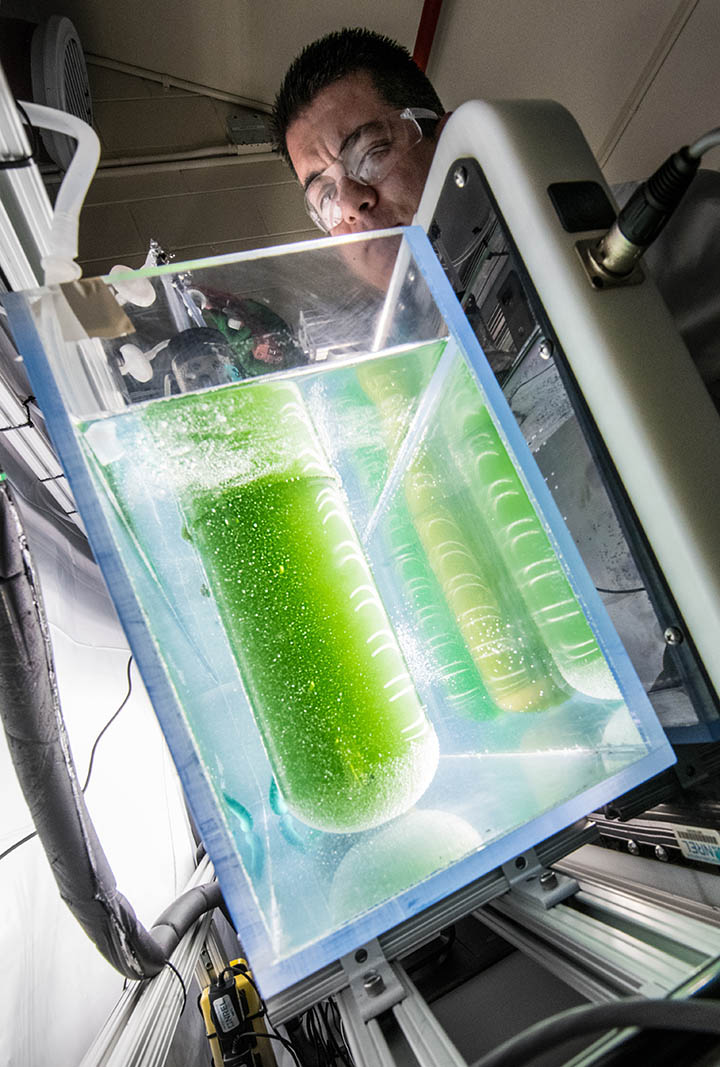

Nick Sweeney thought there must be a better way to cultivate algae, so he came up with one.

“This simple fix makes setting up experiments easier and, more importantly, we are getting better reproducibility and less lost time due to failed experiments that need repeating,” said Sweeney, a research technician who has filed a record of invention (ROI) for his tubular reactor bottle with NREL’s Technology Transfer Office.

Sweeney is not alone at NREL in thinking up ways to improve upon science.

During the last fiscal year, NREL counted a record 233 disclosures — a category that includes 161 ROIs and 72 software records. NREL-developed software is protectable by copyright, while records of invention can be protected with patent applications. The laboratory filed a record 124 patent applications in fiscal year 2019.

“We have seen a significant upward trend for a number of years” for both patents and disclosures, according to Anne Miller, director of the Technology Transfer Office.

The new numbers show a 72% increase in patent applications and a 38% jump in disclosures over a five-year span, from 72 applications and 169 disclosures in fiscal year 2015.

The U.S. Patent Office can take an average of about three years to decide the fate of a patent application. At NREL, the process begins with an ROI submission.

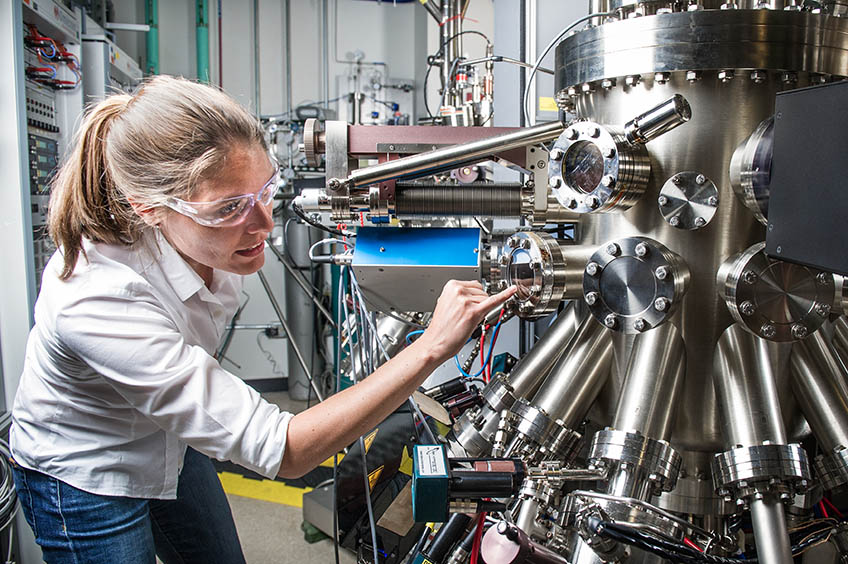

“It’s a pretty easy process,” said Kirstin Alberi, an NREL researcher working in materials science and who holds several patents. “They’ve certainly tried to make it as easy on researchers as possible.” Alberi joined NREL almost a dozen years ago and has seen the process streamlined from mailing in paperwork to simply filling out an online form and meeting with a licensing executive and patent attorney.

Not every ROI leads to a patent application, Miller said. Her office assesses each ROI submitted to determine “whether it has commercial potential and whether we think there would be a market for licensing it.” NREL’s legal department then conducts a separate analysis to ascertain if there’s a reasonable chance of receiving a patent.

“It's this sort of funnel where it goes through these reviews, and then the ones that go forward are a smaller number than the ones that are submitted,” Miller said.

Another telling statistic about the inventive minds at NREL is the number of concept papers submitted to the Department of Energy’s Technology Commercialization Fund (TCF). The Energy Department (DOE), which provides the majority of NREL’s funding, plans to invest as much a $26 million this fiscal year to help commercialize more energy technologies developed at its laboratories. NREL submitted 65 concept papers for possible TCF support in fiscal year 2019, up from 24 the prior year, and submitted 40 TCF full proposals.

“TCF is effectively DOE funding to help NREL partner with industry and de-risk and further mature a particular technology to get it closer to market,” said Eric Payne, senior licensing executive at the laboratory. “Forty TCF proposals indicates that word has gotten out that NREL can partner very effectively with industry and that industry is really interested in pulling ideas out of the lab.”

NREL maintains a website that provides information on technology available for licensing, as does the Department of Energy. “We work hard to lower the hurdles for industry to access NREL inventions, so they invest in the heavy lifting of commercialization,” Payne said.

Commercialization Potential Is Key

Alberi last year filed an ROI that covers a specific use of amber light-emitting diodes, or LEDs. Her team previously discovered a better way to make amber LEDs, which can be combined with red, green, and blue LEDs to produce white light more efficiently. Invited to take part in the Energy I-Corps program, which gets researchers thinking about commercial aspects of their ideas, Alberi was pressed to come up with other potential markets. “We were trying to identify what markets there are, and outdoor lighting was one of them,” she said. “We started brainstorming why that would be important for outdoor lighting and came up with that idea.”

“It’s not something we’re actively working on, but we figure since it popped into our brains, we should put it down in writing,” Alberi said.

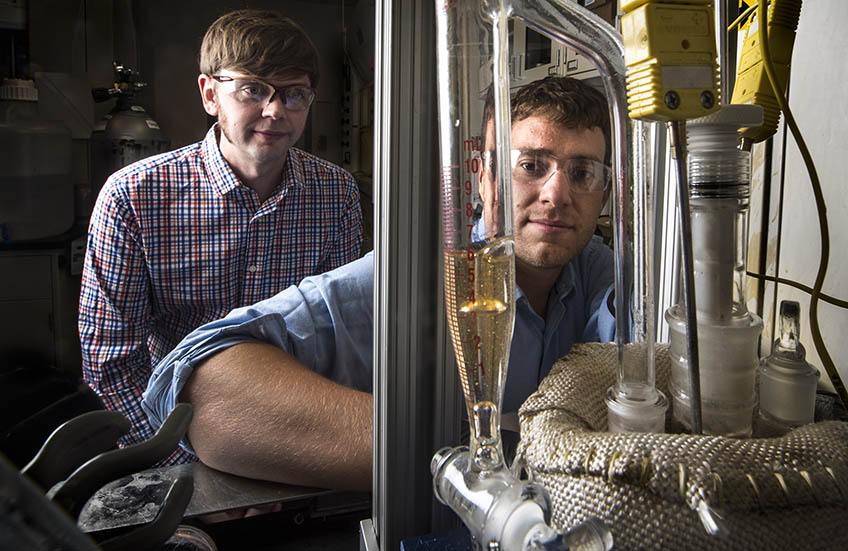

NREL manages Energy I-Corps for the Department of Energy. It was after a stint at Energy I-Corps that Chad Augustine shifted from one idea on how to store energy to another. A colleague, David Young, had come up with the notion of using depleted shale wells as a place to inject compressed air, rather than in underground salt domes as others have tried. The compressed air is released, spins a turbine, and generates electricity. Augustine took that proposal to Energy I-Corps on Young’s behalf but received a lot of pushback on the technical feasibility of using air in shale wells.

Augustine came up with a twist on the original idea: Store compressed natural gas instead of compressed air. The process would be simpler because the gas wouldn’t have to be heated before injection or cooled upon exit from the chamber. This idea merited a new ROI, and NREL filed a patent application.

Computer modeling has shown the idea “will work under the right set of conditions,” said Augustine, who specializes in geothermal analysis. He’s applied for additional funding, including through the TCF, for a pilot project. “It’s proceeded to the point where we think we need to go out into the field.”

Patents Signal a New Beginning

One technology attracting industry interest is a process that would allow a cleaner and greener method to make adipic acid, which is commonly used in industrial processes such as the manufacture of nylon. Gregg Beckham’s research team announced in 2015 they were able to produce the acid from the woody part of plants called lignin. The U.S. Patent & Trademark Office has issued two patents on the process and resulting materials — most recently in July 2019. The researchers participated in Energy I-Corps, and the team is actively seeking licensees for the technology.

Nicholas Rorrer, one of the researchers working with Beckham, took the technology through the Energy I-Corps program. From that experience, he learned, “There is a strong potential for this work, and the sports equipment industry is the target place to start. I think the ultimate goal of this work is to incentivize plastics recycling and help solve our plastics pollution problem.”

As NREL researchers continue working to help solve other energy problems, the laboratory’s ROIs and patent applications will likely continue to set records.

Learn more about NREL’s numerous patented technologies and software solutions available for licensing.

Last Updated Jan. 22, 2026