Lessons in Chemistry From a ‘Healthily Stubborn’ Engineer

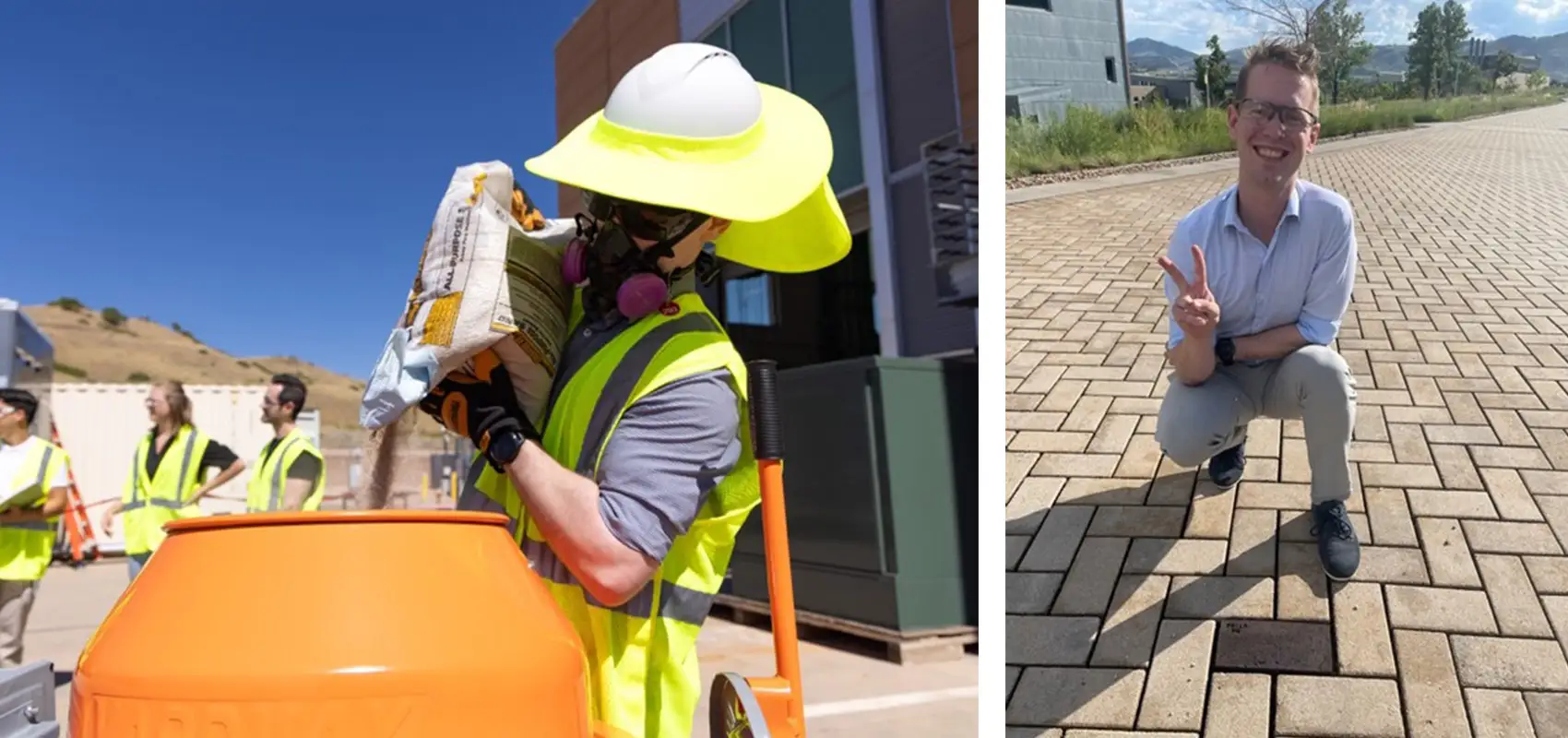

How Paul Meyer’s Polymer Hacks Could Produce Tougher Cement, Safer Engineered Wood, and Less-Energy-Intensive Paper

Paul Meyer loaded the 10-foot-tall trebuchet onto a flatbed trailer—not alone, of course. The wooden medieval siege weapon weighed about as much as Meyer plus another team member on their Advanced Placement Physics pumpkin-tossing team.

Hence the flatbed.

The day before, the high school troupe tested their trebuchet at a local park. A few nervous parents called the cops (not keen on pumpkins flying near their kids), but the first tests went well. The pumpkin sailed 100 to 200 yards. A win seemed sure.

“We did not win,” said Meyer, a researcher in the Building Energy Science Group at the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR).

After backing their trebuchet trailer up to the football field, Meyer and team wheeled it—yes, theirs had functional wooden wheels—next to their classmates’ catapults, air cannons, and other flinging machines. Then, one by one, each loaded in a pumpkin and chucked it as far as it could go. Meyer’s pumpkin plopped down somewhere between 20 and 50 yards, short of a win.

“The trebuchet was definitely the superior choice if you could build it well,” Meyer said. “The thing is: It’s more complicated to build.”

Meyer does not shy away from complicated. The chemical engineer prefers projects that straddle the skeleton-filled divide between theory and application—or, as Meyer put it, “really weird, cool new science” and “the connection to industry.”

And humdrum discoveries are not enough.

“I want sweeping change. I like projects that, if they succeed, would change the world's economy by an order of magnitude,” Meyer said.

How? Meyer’s chosen tools are polymers, the large molecules that build every essential from our DNA to materials, like plastics, textiles, ceramics, and even microelectronics. And Meyer’s polymers could cut energy demand for paper production, form a super tough and affordable cement alternative, and make a formaldehyde-free engineered wood—or all three at the same time. That is the beauty of this new polymer.

“I like to joke that I insert polymer chemistry into places that no one asked for,” Meyer said.

In the latest Manufacturing Masterminds Q&A, Meyer shares what it was like to earn a Ph.D. in just 3.5 years, why market research is a critical part of technology development, and how to build a stronger kind of cement that is just as affordable. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

How did you get into science in the first place?

My mom is a science teacher and wanted to put me in all the advanced educational things. My father was in the River Parks authority where I grew up in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and that exposed me to things like civil engineering. Ever since I was in middle school, I gravitated toward engineering because I thought it was cool to learn how the world works and then go do useful things with those principles.

Did you go straight for chemical engineering?

I dabbled a lot in chemistry, some electrical engineering and programming. I also got a minor in physics. I thought I wanted to go into quantum computing at one point. But I didn't. For physics, the timeline for making an impact seemed a lot longer and the applications were a lot more niche than pop culture leads you to believe. I ended up in chemical engineering because it’s one of those “engineerings” where you can kind of do whatever the heck you want.

How did you end up in polymers?

For grad school, I specialized in polymers because I really liked my main advisor. I worked on material—a photoresist—that’s used to draw circuits on computer chips. If we can add in a bit of magic sauce, you can reuse old, extremely expensive machinery to build the next few generations of electronics and get more bang for your buck. That would be huge.

The other main project had to do with block copolymer self-assembly—effectively two different polymers that are stuck together and form unique shapes at the 10-nanometer scale. With some modification, we put ours into batteries and water- and gas-separation membranes. We found some promising results but had limited success since we only had six months before my advisor was like, “I’m ready to retire.”

I graduated with my Ph.D. in 3.5 years. It was a very stressful time. I have a vivid memory of doing 80- or 100-hour weeks where I did nothing but write my thesis. I had a little blow-up mattress for whenever I needed a small mental breakdown, so I could go lay down and then get back to it 30 minutes later.

Wow. And then after that, you came straight to the National Laboratory of the Rockies. What attracted you to the lab?

The lab’s goal is to be the bridge between academia and industry, and I really liked that. I want the freedom to do really weird, cool new things but also the connection to industry so I can make an impact. If your cool thing doesn’t make it in the market, then who cares? Here, we have the practicality piece and the really cool science piece. And I like to operate where those two things overlap.

How are you merging those two worlds now?

I’ve kind of defined my career around trying to insert polymer chemistry into every area of engineering.

Ha! Like where?

I have two main projects right now. The first is the paper drying project. Taking water out of paper consumes about half a percent of the world’s energy.

To put that in context, that’s enough energy to run 20% of Texas, right?

Right. Just drying paper. We make a lot of paper. There’s a lot of water in that paper. And it takes a lot of energy to evaporate water. I got hired to do thermal responsive polymers for desiccants. Below a specific temperature, these polymers suck water in. And above a specific temperature, they’ll squeeze water out. So, what if we take this polymer and smack it against paper. Will it dry? The answer appears to be yes. And your energy consumption drops 90% or 95%.

That’s huge!

It’s cool, right? All science-y and stuff. But you have to make it work in the real world. It needs to be fast. Normal paper drying happens in about 6 seconds, and the paper is going 60 miles an hour. Our material dries in about 30 seconds. So, now you have a classic capital expenditures versus operational expenditures trade-off. The paper mill is not going to slow down. The polymer belt lifetime also needs to be about a year—which is likely to be millions of cycles—for it to be economical. Our current work revolves around addressing those things. We also need to integrate this into existing manufacturing. No one is going to build a new paper mill for your polymer.

Where else are you inserting polymers?

Cement and concrete. Every year, the world makes at least 50 million tons of lignin, a tough kind of polymer that’s found in plants. Then they burn 98% of that because they don’t have a better use other than as a low-value fuel. We wondered if there could be a better use for this material that plants spent years building.

But concrete is some of the cheapest stuff in the world. So, whatever we make needs to be cheap to compete. Lignin fits the bill. It’s still too expensive by itself, so we add in aggregate, a filler material, just like we do with concrete. Our lignin resin is the binder, just like cement in concrete, and we add rocks to add strength and dilute the cost, like in concrete.

Concrete is also known for its strength. But epoxy resins are stronger. So, what if we took this lignin material and cross-linked the heck out of it—bound these polymer strings together—so it acts like an epoxy? Imagine you get gum in your hair—that cross links all your hairs together. But instead of a big wad, you have microscopic particles of gum all throughout your hair.

What a nightmare.

Yeah, you’d have to shave your head. But we want that nightmare. That nightmare makes the material very durable and robust. We selected a few materials—add in a big smacking of luck—and popped out a thing that was cross-linked. We think. It’s gotten up to about 14,000 pounds per square inch (psi) strength. Most concrete materials are between 3,000 and 4,000 psi. You only need 8,000 if you’re building something like a 50-story skyscraper. So, we have the strength. And there are some clear pathways to get to cost parity.

That’s very exciting. Any other materials you’re polymer-hacking?

Wood. Normally, you use formaldehyde-based resins to make engineered wood. But formaldehyde can cause cancer. Your furniture, wall panels, or floor panels can be made of this stuff. Our lignin-based binder has no formaldehyde. In fact, the components are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to be eaten. Lignin is in all plants. If you have a healthy diet, you eat it every day. Initial results suggest the use of this lignin-based binder in engineered wood materials is already cost competitive. We may actually be cheaper than current-day materials.

What advice would you give to folks who want to follow in your footsteps?

Be stubborn—in a healthy way. Be healthily stubborn; it’s a balance between stubbornness and knowing when to pivot. You’re going to fail a lot. That’s the nature of our work. We’re in the highest-risk, highest-reward kind of business. Success also comes from being surrounded by good people. Behind these projects, there’s a whole team that helped them accumulate into success.

You’re just one part of a polymer, really.

I am a monomer unit, just one part of a larger polymer. And I’m extremely grateful to the other monomer units I work with.

Read other Q&As from NLR researchers in advanced manufacturing, and browse open positionsto see what it is like to work at the National Laboratory of the Rockies.

Last Updated Jan. 22, 2026