Scientists Describe Exciton Formation in Thin Magnetic Crystals—With Potential for Quantum Computing or Other Advanced Technologies

When Exposed to Light, Excitons Form on the Surface and in the Bulk of Layered Ultrathin Magnetic CrSBr Films—Fundamental Knowledge Essential for Controlling Them

Some fundamental science is so complicated—so steeped in abstraction—that conducting experiments is not enough. Experimentalists need theorists to turn raw data into recognizable pictures of what is happening below the surface.

Nowhere is that truer than in condensed matter physics, a field focused on subtle behaviors of electrons and subatomic particles that spin, orbit, and oscillate through our dynamic material world. Such phenomena are sometimes hard to detect or understand with current experimental techniques.

Since the 1990s, scientists have relied on models to try and understand these quantum phenomena, but not all experts agree on their core assumptions. To remove the guesswork, researchers often pair lab experiments with theory derived from first-principles quantum calculations—work provided by people like NREL theorists Mark van Schilfgaarde and Swagata Acharya.

“The problem is often interpreting experimental results in these complex systems, and that's what the theory does,” NREL Chief Theorist van Schilfgaarde said. “You can use the theory to probe things that are difficult to directly observe through experiments. It’s a way of describing optical and magnetic properties without recourse to models that may overlook fundamental quantum phenomena because they rely on inaccurate assumptions.”

Explaining unusual magnetic and optical properties with theory was the impetus behind a 2025 Nature Materials article, with contributions from NREL’s van Schilfgaarde and Acharya with support from the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences. A team of experimentalists and theorists from Columbia University, Technical University of Munich, Dresden University of Technology, King’s College London, Radboud University, University of Chemistry and Technology Prague, University of Regensburg, and NREL discovered unusual exciton behavior of ultrathin magnetic films made from chromium sulfide bromide (CrSBr).

The team was able to study excitons in layered CrSBr films thanks to a rigorous combination of experimentation and high-fidelity theory unique to NREL’s Questaal electronic structure package, which let them better understand experimental observations.

The results provide fundamental insights into a highly specialized class of materials that could help engineers eventually harness, tame, and manipulate excitons for quantum computing, photonics, spintronics, and other advanced technologies.

What Is Exciting About Excitons?

Like the bit behind classic computers, quantum computers use quantum bits—or qubits—to represent the flow of information. Like the on or off position of a light switch, a bit can only be in one of two states: 0 or 1. Qubits can also be 0 or 1, but they can also be in superposition of both 0 and 1 simultaneously, like a dimmer light switch with limitless settings. It is the quantum superposition of qubits that will enable quantum computers to someday perform calculations far beyond the reach of even the fastest supercomputer today.

Researchers have proposed many approaches for creating and controlling qubits. But another possibility has recently emerged: designing materials that let researchers intentionally create and control excitons.

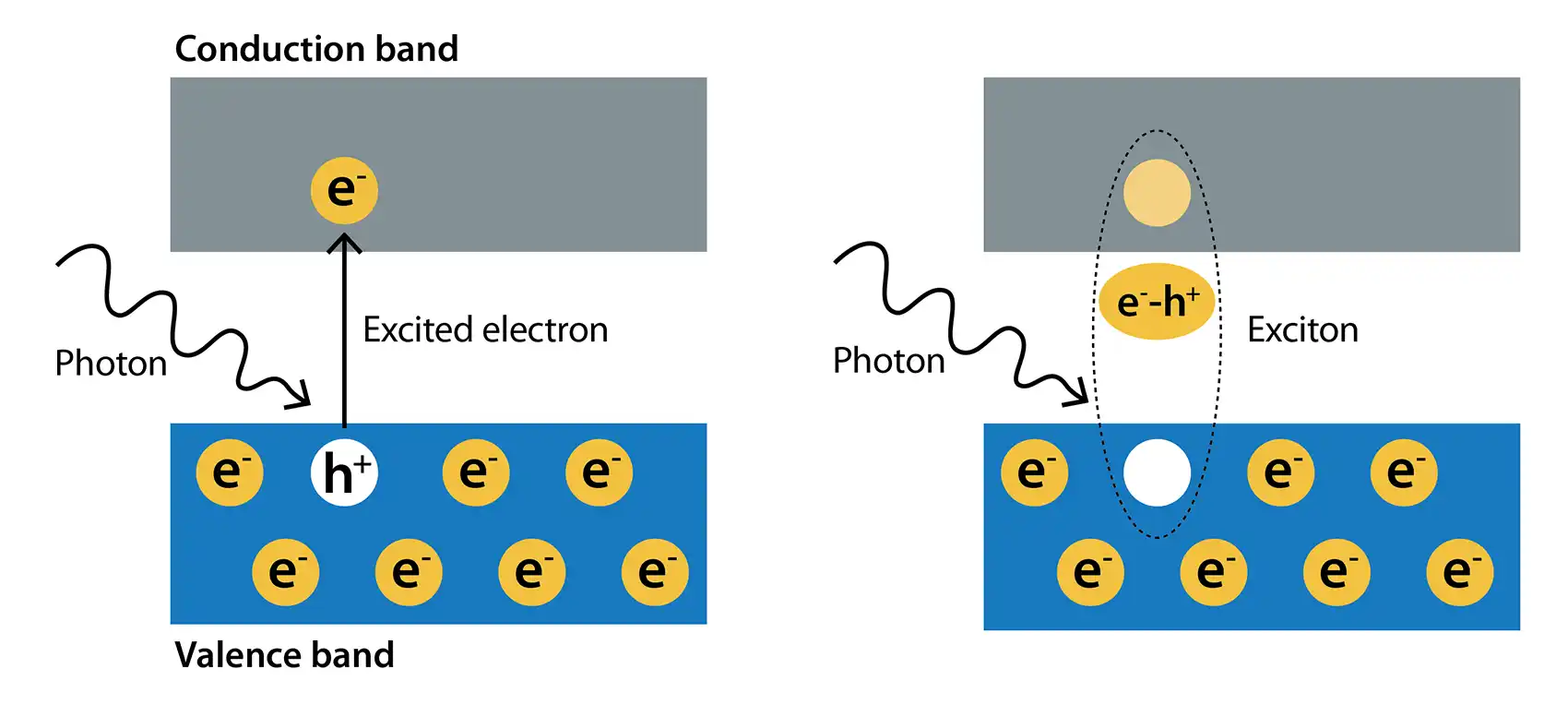

What is an exciton? When an electron is excited by a photon, it jumps to a higher energy level, leaving behind a “hole” or missing electron. Attracted by opposite charges, the electron and hole bind together by an electrostatic Coulombic force. They pair up without recombining, forming an exciton that behaves like an uncharged particle called a quasiparticle.

Scientists proposed the concept of excitons in the early 1930s. Only recently have researchers begun exploring the behavior of these quasiparticles in two-dimensional magnetic systems. Some have posited that applying and removing a magnetic force could cause excitons to split and then return to equilibrium. This splitting divides excitons into two or more distinct energy levels, changing their optical and electronic properties.

“That slight splitting could form a two-level quantum system,” van Schilfgaarde said. “You have one state that’s slightly higher energy than the other, and that two-level system can form the basis for a qubit in a quantum computer.”

More Knobs To Turn: Distinct Surface and Bulk Excitons Form in Ultrathin Magnetic CrSBr

In practice, using excitons as qubits will require a fundamental understanding of their behavior. The excitons must form and perform consistently and predictably if engineers ever want to control them, whether as qubits for quantum computers or to generate and control spin currents in other advanced quantum devices.

Discover Other NREL Research on CrSBr

Hyperbolic Exciton Polaritons in a van de Waals Magnet, Nature Communications (2023).

Paramagnetic Electronic Structure of CrSBr: Comparison Between ab initio GW Theory and Angle-Resolved Sectroscopy, Physical Review B (2023).

Giant Exchange Splitting in the Electronic Structure of A-Tyle 2D Antiferromagnet CrSBr, npj 2D Matierals and Applications (2024).

Magnon-Mediated Exciton-Exciton Interaction in a Van der Waals Antiferromagnet, Nature Materials (2025).

Could CrSBr be the materials basis for such applications? To find out, Acharya and van Schilfgaarde have worked with collaborators over the past few years to untangle the fundamental science at play—producing a series of articles on CrSBr.

In this latest study, the team turned its attention to another puzzle: Theorists and experimentalists have noted excitons at 1.34 electron volts (eV) and 1.36 eV in CrSBr, as measured by optical spectroscopy. Some posited that CrSBr’s magnetic properties could explain the two energy peaks, but they lacked the theory to explain exactly why and where excitons were forming.

To fill the gap, Acharya and van Schilfgaarde used NREL’s Questaal software suite to perform complex calculations and ultimately describe the complicated quantum mechanics at play. Columbia’s reflectance spectroscopy and photoluminescence measurements confirmed their calculations.

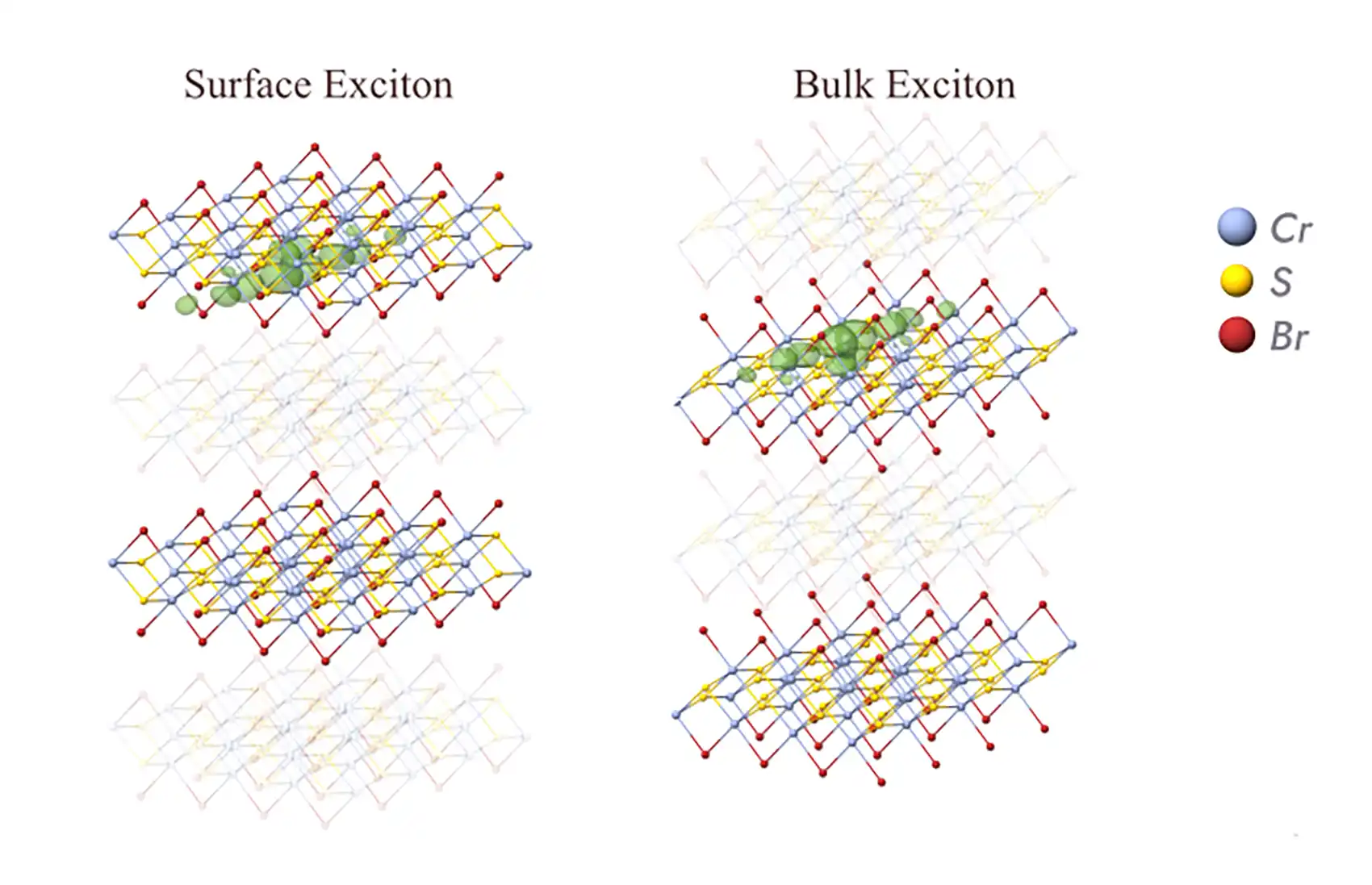

Their approach pointed to a clear conclusion: because of the material’s antiferromagnetic properties, excitons form on the surface of CrSBr at 1.34 eV—distinct from excitons within each of the bulk layers at 1.36 eV.

“The surface excitons interact with only one layer, and bulk excitons are sandwiched in between two layers. At the surface layer, the electron cloud is weaker and the electron–hole interaction is less screened, making it larger,” Acharya explained. “The larger the interaction the more strongly bound the excitons. The difference in the binding energies of these two excitons purely emerges from this effect. As a result, the surface excitons and bulk excitons become two different entities.”

The exciting result, Acharya said, was that even as layers of CrSBr were added, the energies of both the surface and bulk excitons remained constant.

“The surface exciton brightness did not change when adding more layers, while the bulk exciton brightness increases with the addition of more layers,” he added.

That result sets CrSBr apart from other interesting materials, like MoS2 and black phosphorus, where exciton energy decreases as the number of layers increases. Even when grown at a thickness relevant for commercial applications, CrSBr forms and maintains high-energy excitons. Plus, the surface and bulk excitons respond to light independent of one another—a surprising result, which the theory was able to explain.

“What makes CrSBr special is that as a magnetic system it also has spin,” Acharya said. “When combined with the two types of excitons, that spin can result in many states between 0 and 1 to facilitate quantum superposition. This combination gives CrSBr added functionality that never existed before. It means engineers have more knobs to turn and variables to adjust when designing new technologies.”

Of course, it is too early to say what exactly these results might mean for the future of CrSBr in quantum computing or other optoelectronics applications. What is clear is that CrSBr offers a unique combination of strong excitonic effects, magnetic tunability, and air stability, making it a versatile material for a wide range of advanced technologies.

For now, however, the observations themselves are notable enough.

Using a powerful combination of theory and experiments, van Schilfgaarde and his colleagues have shown it is possible to understand exciton formation and behavior in CrSBr—with more research on the horizon. Can the theory universally predict quantum effects in other materials? In the global race toward advanced technologies, insights like that are just the thing researchers need to gain a competitive edge.

Learn more about NREL’s Questaal software suite and about the U.S. Department of Energy’s Office of Basic Energy Sciences. Read “Magnetically confined surface and bulk excitons in a layered antiferromagnet” in Nature Materials.

Last Updated May 28, 2025