Beneath the Surface: Why Bri Friedman Embraces Failure

An Engineer Looks Back on High School Science Fairs, African Drone Flights, and Marine Energy Innovations That Shape the Future

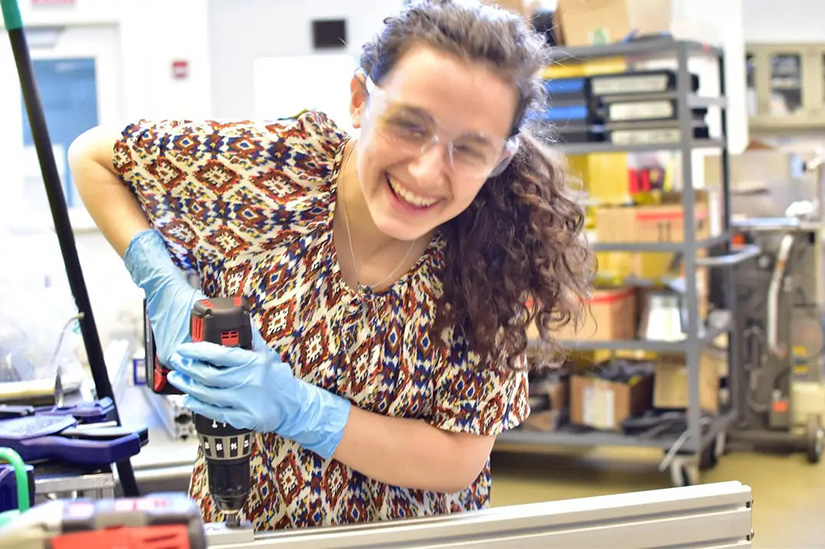

Bri Friedman is looking forward to learning from failure.

This National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) engineer is working with the laboratory’s marine energy team to develop a device called the small underwater research flap wave energy converter—or SURF-WEC, for short.

SURF-WEC takes the form of a submerged flap that swings back and forth to capture energy from ocean waves to power an electric generator. In the coming months, SURF-WEC will undergo a design review, in which a team of experts and stakeholders will evaluate the device to determine whether it is ready for deployment. If the design review goes well, Friedman and her team, in partnership with the University of Hawaii, will send SURF-WEC on an experimental deployment off the Hawaiian coast for up to one year.

“‘Up to’ are the key words—we expect the system to fail within the year,” Friedman quipped, “but we are eager to learn from those failures and share our lessons with our colleagues in marine energy.”

Of course, Friedman and her team also want to understand what works well during the SURF-WEC deployment. However, as Friedman went on to explain, the success of the SURF-WEC deployment is not tied to the amount of energy the device can capture or the length of time the system can operate without issue. Instead, the goal is to collect data and learn which decisions contributed to setbacks and which led to success—and to share those lessons with the marine energy community to help reduce the risks and costs of future deployments. To that end, the team will make the deployment data, along with data collected during SURF-WEC’s laboratory testing and simulation stages, publicly available on the Marine and Hydrokinetic Data Repository.

As any marine energy researcher or technology developer knows, harnessing energy from ocean waves is a big challenge. Many WECs fail in the harsh ocean environment due to the corrosive effects of briny seawater, constant wear and tear from crashing waves, impacts from floating debris, or even the accumulation of barnacles, algae, and other marine life. Designing WECs to withstand these challenges requires strong materials, backup systems for important parts, and regular maintenance. For Friedman, tackling these challenges feels surmountable—thanks to the NREL marine energy research team’s collaborative spirit.

“I feel like we each have a pickax, or maybe a ladle, since we’re talking about the ocean,” Friedman said. “We’re each ladling out a little bit, doing our part to make marine energy a viable, usable resource.”

From Science Fairs to Drone Flights

Friedman can trace her career path back to middle school, when she first decided she wanted to be an engineer when she grew up. The youngest of four children—two of whom went on to become mechanical engineers—Friedman grew up immersed in science, with a strong desire for discovery.

“It wasn’t always a popular sentiment when I was young, but I genuinely enjoyed participating in science fairs,” Friedman said. “They gave me a chance to experiment, make predictions, and learn by doing, which would further spark my curiosity.”

That love for hands-on learning led Friedman to get involved in robotics in high school, which became her main after-school activity and solidified her desire to pursue a career in engineering. At the same time, she felt a strong pull toward next-generation technologies and types of work that could protect people’s health and well-being.

“I wanted to find a job that both scratched my scientist itch and aligned with my values,” Friedman said.

Friedman followed her passion for scientific experimentation to Virginia Tech, where she pursued mechanical engineering for both her bachelor’s and master’s degrees. As an undergrad, she interned at NREL through the Science Undergraduate Laboratory Internship (SULI) program, working with a research team to create a photoluminescence system for testing silicon solar cell processing methods. This was not only a valuable learning experience; it also supported Friedman’s commitment to making a positive impact on the world.

“It was so exciting to learn how to harness energy from nearly boundless sources like the sun, wind, and water,” Friedman recalled. “Plus, everyone I encountered during my internship seemed happy to be at NREL, which made me even more excited about the work. The SULI program showed me a career path that I was really excited about.”

During her master’s program, Friedman worked as a graduate research assistant with the African Drone and Data Academy, a program that trains recent college graduates to design, build, and pilot drones for agriculture, medical equipment delivery, and other humanitarian efforts in Africa. Friedman taught the program’s first cohort, delivering lectures, supervising lab work, and providing one-on-one drone flight instruction. Near the end of the academy’s first course, Friedman visited a refugee camp and had an experience that would become the foundation for her master’s thesis.

“My graduate research focused on using drone imagery to develop a flood model for a low-resource area,” Friedman recalled. “In developed countries, flood models are built using years of historical data, but in low-resource areas, that kind of data is rarely available. Our challenge was to generate a useful flood model without waiting for years of data collection.”

To fill this data gap, Friedman’s team used drones to capture high-resolution aerial images of the camp. Friedman then used this imagery to create a flood model, validating its accuracy by comparing the model’s prediction to locations where homes had collapsed due to flooding.

“The refugee camp was overpopulated, and many of the homes were built from clay wherever there was available space, so they collapsed easily due to heavy rains and few drainage paths,” Friedman explained. “The collapsed structures showed where flooding had actually occurred, which helped us confirm that the model had accurately predicted those high-risk areas.”

From Drone Flights to Wave Power

Unfortunately, the coronavirus pandemic cut short Friedman’s time in Malawi. She returned home in March 2020 after the first group of students graduated but continued to support her students through online instruction. In addition, her experience with drones set her up for her next move: After finishing her master’s program in 2021, Friedman landed a position as a postgraduate researcher with Pacific Northwest National Laboratory’s (PNNL’s) water power engineering team, which was exploring ways to integrate drones into their projects.

Shortly after joining PNNL, Friedman began working on a project to support the development of a triboelectric nanogenerator—a small device that converted the motion of ocean waves into electricity using static charge buildup. Intended for deployment in the Arctic Ocean, the device would provide a low-maintenance power source for ocean monitoring equipment. Friedman also studied ways to use the temperature differences between surface water and deep water to generate energy for an underwater glider, a type of autonomous underwater vehicle that navigates the ocean by changing its buoyancy to move up and down through the water.

After two years in Richland, Washington, where PNNL is located, Bri was ready for a change of scenery. She kept an eye out for opportunities at NREL and, in 2023, moved to Colorado to work as a full-time researcher on NREL’s marine energy team. The move brought Friedman full circle—in more ways than one.

Back in 2017, when Friedman was working on the application for her internship at NREL, she read up on NREL’s work and learned about different types of WECs, including those that flap back and forth, similar to SURF-WEC.

“Reading about these types of WECs, I thought, ‘Wow, it would be amazing to work in that field,’” Friedman recalled. “Eight years later, I do work in that field—on a project very similar to the ones I read about.”

In addition to SURF-WEC, Friedman contributes to several other marine energy projects at NREL. Her work involves testing, characterization, and outreach, helping researchers and industry partners better understand and utilize emerging wave energy technologies. She has worked with the large-amplitude motion platform, or LAMP, a simulation tool that replicates a WEC’s response to different ocean wave conditions in a controlled environment. She also supports the Power at Sea Prize, which encourages innovative marine energy concepts by lowering barriers to entry for new developers.

“We have a mix of participants—some from universities and some independent teams,” Friedman said. “It’s been great to see such a broad range of people engaging with marine energy innovation.”

Time To Root Down

Friedman lives in Boulder, Colorado, a short drive from her work at NREL’s Flatirons Campus. She misses her family, who still live on the East Coast, but relishes the time she gets to spend with her four young nieces.

“I definitely aspire to be the fun aunt,” Friedman said.

With a population of about 105,000, Boulder is the biggest city Friedman has lived in during her adult life, but it feels like the right fit.

“Boulder is a bigger city than what I’m used to, but there’s plenty to do, which I appreciate,” Friedman said. “I especially enjoy the rock climbing and general outdoor adventuring shenanigans.”

The move to Colorado has also given Friedman a chance to create a more long-term community for herself.

“Before moving to Colorado, I spent over two months living in my car, climbing and exploring the outdoors,” Friedman recalled. “It was an amazing experience, but the communities I encountered during that time always felt temporary. Since moving here, I’ve been working on putting down stronger roots.”

Friedman’s work at NREL feeds her desire for community as well. She appreciates the collaborative spirit on her team, in which everyone is working toward a common goal, even if they are focused on different projects. In addition, being on campus every day has helped Friedman build connections through casual conversations, strengthening her sense of belonging.

“We share successes and failures, and I really value that sense of teamwork and collective learning,” Friedman said. “It’s a great feeling to know we’re all working together toward a shared purpose.”

Learn more about how NREL’s experts are helping advance marine energy. And subscribe to the NREL water power newsletter, The Current, for the latest news on NREL's water power research.

Last Updated May 28, 2025