With Inverters, An Island Adapts to Changing Physics of Power Grids

National Laboratory of the Rockies Helps Kauai Tap Into a New Source of Strength That Can Stop Electric Oscillations

Kauai, one of the most remote islands of Hawaii, stands steady among the timeless crash of ocean waves. Electric waves, however, almost crashed Kauai’s power system in an instant.

Kauai consistently provides among the lowest electricity rates of any island in Hawaii thanks to Kauai Island Utility Cooperative’s (KIUC’s) addition of new power sources, many of which rely on electronic devices called inverters.

But with more inverters on their system, KIUC identified grid oscillations they had never seen before—not the normal 60 Hertz frequency, but an imbalance of energy across the island. If left unchecked, the oscillations could cause reliability problems, power outages, and equipment damage.

As power systems around the world integrate inverters, they are entering a new physics of operations. The new physics mixes electromechanics and power electronics—machines and semiconductors—and it just happens that the isolated utility KIUC is one of the first places to face these challenges at scale.

Over three years, a team led by the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR), a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) national laboratory, investigated Kauai’s oscillations with every tool available and others they had to invent. They not only found the source and solutions to the problem but also developed a general framework that any utility can use to stabilize and strengthen its grid using modern, power-electronic-based resources.

National Laboratory of the Rockies researchers and Kauai Island Utility Cooperative workers tour a control room on Kauai's south shore. Photos by Connor O'Neil, National Laboratory of the Rockies

A Warning Ripples Through

As an electric cooperative, KIUC is small and remote enough compared to other utilities that it can try new strategies with less risk and more freedom, but large enough that it provides lessons to utilities all around. Being a small utility, it also needs to keep solutions as simple as possible.

“We still manually decide which units come online. We do dispatch calls over the radio and calculate the day-ahead generation with a spreadsheet,” explained Richard “RV” Vetter, KIUC’s Port Allen power station manager.

Even as Kauai added more inverter-based power and battery storage throughout the 2010s, the operators used their intuition to keep the grid operating correctly.

“Our requirements for operation were informed by our experience with our grid,” said Brad Rockwell, chief of operations at KIUC. “We know how low our voltage dips during transient events, and we know which settings will keep the grid stable. This is our system—we know how it works.”

But in November 2021, what happened on the grid defied its operators’ intuition.

At 5:30 a.m., the island’s largest gas generator unintentionally tripped offline, as generators occasionally do, causing island-wide frequency to dip. The inverter-based plants on the island automatically ramped up power to restore frequency, but an oscillation appeared that caused frequency and voltage to wobble throughout the island.

Power lines transmitted electrical oscillations back and forth on 33-mile-wide Kauai island. The oscillations compelled Kauai Island Utility Cooperative to study its grid stability and, with NLR, deploy stabilizing controls with battery systems. Photos by Connor O’Neil, National Laboratory of the Rockies

Twenty times a second, an electrical wave sloshed through transmission lines, pushing the frequency near to prescribed limits and dropping around 3% of customers off service until it dissipated a minute later.

While this disruption was not disastrous, it was a warning. The oscillation prompted KIUC to seek the help of long-time partner NLR, which soon after launched the DOE-funded Stability-Augmented Optimal Control of Hybrid PV Plants with Very High Penetration of Inverter-based Resources (SAPPHIRE) project, focused on addressing the challenges experienced in Kauai and beyond.

Searching for the Source

Oscillations like Kauai’s are not entirely mysterious to the power sector. They have been reported globally and are evidently on the rise. Despite this, each one is studied like an individual anomaly, not an emerging trend. Operators lack a standard policy to treat the problem.

“When we first jumped into Kauai’s grid, there was no general framework for industry to solve the oscillation problem. These kinds of issues are usually first seen on small, isolated grids, so Kauai gave us an important chance to understand stability,” said Jin Tan, project lead at NLR.

“First, we asked, ‘What does the real data tell us?’” Tan said.

Her team gathered KIUC’s historical data from phasor measurement units and digital fault recorders—common grid sensors—which they used to identify the origin of the oscillation: two inverter-based power plants.

Photo by Bryan Bechtold, National Laboratory of the Rockies

“But data alone has limitations,” Tan explained. “You can only see which plant is causing the oscillations, not how. So, we leveraged model-based methods, too.”

They built not just a model of Kauai but the highest-detail electromagnetic-transient model possible—something that is rarely done by utilities when commissioning new generators, but that could reach the root of the problem.

This animation of Kauai's power system recreates the oscillations that occurred on the island in November 2021, using real data from the event. Frequency begins to oscillate after a synchronous generator trips but is eventually arrested. Using this visualization and event analysis, the Kauai Island Utility Cooperative and NLR identified the instability source and a suitable improvement. Video by National Laboratory of the Rockies

Using the model plus the data, NLR’s team reran the event many times, discovering which inverter settings were instigating the oscillations. Purdue University helped validate the findings via small-signal analysis while NLR’s team validated it with hardware testing using the NLR ARIES platform.

All said, the team had built a miniature Kauai grid in Colorado, replicating everything down to the exact same inverter model. Thanks to such exhaustive modeling, NLR now had the capability to test new inverter controls and verify their stability before deployment in the field, and Kauai now had a solution to prevent future oscillations.

They did not have to wait long to discover if it worked.

NLR built a scaled-down version of Kauai's grid using the ARIES platform. With this mock power system and real event data, they modeled the moment Kauai’s grid suffered an electrical oscillation. This allowed the team to determine optimal inverter settings for Kauai to avoid similar events. Photo by Josh Bauer and Bryan Bechtold, National Laboratory of the Rockies

Electronic Stability Is Put to the Test

Coincidentally, in 2023, the same large generator tripped, just like two years prior. The same electrical wave shot through the Kauai grid, and the same inverter-based plants responded. This time, no oscillation occurred.

The difference was that grid-forming controls had been added to the inverters—a paradigm shift in how power systems derive strength and stability.

“We’ve gotten to the point where inverters are dominating our entire resource mix,” Rockwell said about KIUC. “Here in Hawaii, we have very limited resource options in the first place, and, without a doubt, inverter-based resources are the cheaper option.”

First fueled by burning sugarcane waste, then oil, then broadening to hydropower, biomass, then inverter-based resources, Kauai has continually searched for a resource mix to reduce costs and improve robustness to wildfires. To that end, KIUC has grown its inverter-based supplies, often running hours of the day on domestic generation alone.

But as KIUC found, inverters have different electrical characteristics, which manifest at the levels reached on Kauai. Most evident, inverters lack the mechanical inertia of spinning generators, which historically steadied power fluctuations.

Left: KIUC’s Richard “RV” Vetter, KIUC’s Port Allen power station manager, stands by a generator shaft under repair. Right: The oil-fired generator that tripped initially triggering the grid oscillations. Kauai island still contains oil-fired generation for baseline power and also uses technologies like synchronous condensers, which are spinning reserves that supplement mechanical inertia. Photos by Connor O’Neil, National Laboratory of the Rockies

“We’re ending up with a grid that’s basically a bunch of synchronized computers,” stated Andy Hoke, principal engineer at NLR.

Hoke has been analyzing the new physics of power systems for over a decade, and he helped KIUC identify the grid-forming inverter settings they needed to restore grid strength.

“A grid-forming inverter doesn’t try to measure frequency and voltage and respond; rather, it just tries to hold its own frequency and voltage constant,” Hoke explained.

It is a form of synthetic inertia—something to make up for less mechanical inertia.

“For those grid-forming inverters to act like synchronous machines is very important to us. The fact that we can lose a synchronous machine while these grid-forming inverters stay on means we don’t go black,” Rockwell said.

A Probe Into Power System Stability

A far-reaching lesson from Kauai is that grid stability is a central, quantifiable, grid commodity. Just as utilities buy electricity from power plants, they can procure stability. This is an outcome of the new, electronic-based physics of power systems. But to work in practice, it requires one important piece.

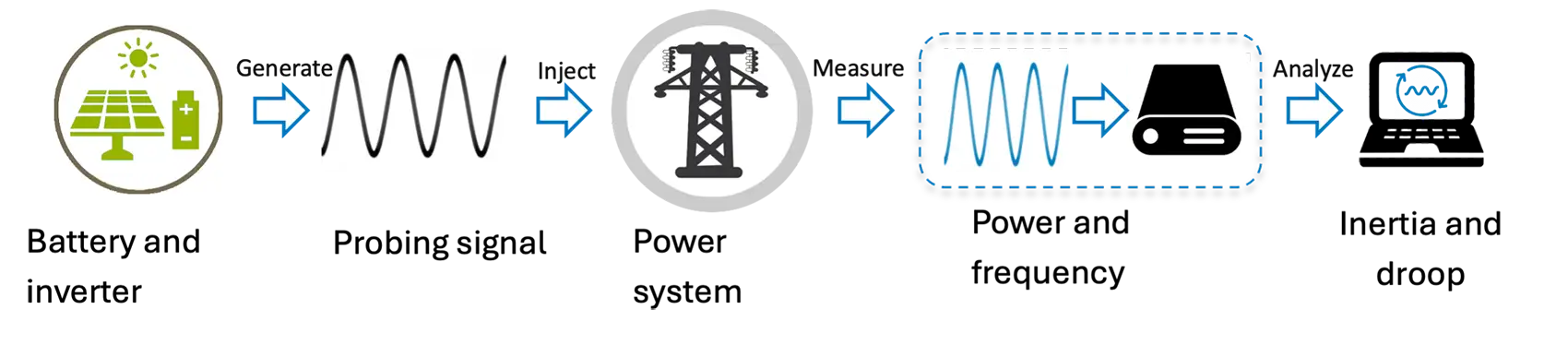

“Operators need the ability to estimate stability on their system,” Tan said. “Many operators have seen growing costs from managing stability factors, such as rate of change of frequency. Now that we have proven how inverters can provide stability, we need to show by how much.”

To cap their collaboration, Tan and team took on this final challenge of estimating real-time stability, and they did so in a way that no one had done before: by probing the power system.

The method developed by NLR and partners to measure the real-time grid inertia—and consequently, its strength—is depicted here. A small electric signal is emitted by a battery plant, and its modulation by the grid is then measured by software in the operator’s control room. Graphic by National Laboratory of the Rockies

With KIUC’s consent, NLR sent small pulses through Kauai’s grid using an inverter-based plant owned and operated by AES Hawaii. By measuring the pulse throughout the grid with custom sensors from partner UTK, Tan’s team could estimate how resources react to an instability. In effect, they could calculate each generator’s inertia, physical or electronic, and its contribution to overall stability.

“We found that grid-forming inverter-based resources significantly enhance grid stability,” Tan concluded.

Firm power—that is, strong, stabilizing power that every grid needs—can be found beyond mechanical generators. The three-year effort by Kauai, NLR, and partners demonstrated that power electronics can be equally capable of offering essential grid stability services. In fact, they can offer an even greater range and responsiveness of services than machines.

Although Kauai is a remote island, its electrical issues are not so remote. Findings from island systems may inform grid planning in other contexts, too.

“It will not require technologies that are far more advanced than what we already have,” wrote Hoke and NLR Power Systems Engineering Center Director Benjamin Kroposki in an IEEE Spectrum feature. “It will take testing, validation in real-world scenarios, and standardization so that synchronous generators and inverters can unify their operations to create a reliable and robust power grid. Manufacturers, utilities, and regulators will have to work together to make this happen rapidly and smoothly.”

Strength in Unity for the Power Sector

To sum up, the SAPPHIRE project found the source of Kauai’s grid oscillations, validated and proposed a solution, witnessed its success, and then developed a way to measure instantaneous grid strength. The forthcoming report will provide even more detail and describe how inverter-based grids can provide affordable and reliable energy to customers.

“This is a huge success,” commented KIUC Engineering and Technology Manager Cameron Kruse.

“Inverter-based resources—that’s our bread and butter for stability. Pre-2012 we used to load-shed twice a month; now we rarely do. We’ve microgrid-ed through the July 2024 Kaumakani wildfire with this system. Our vision of reliable, low-cost, safe power delivery hasn’t changed, but our how has,” Kruse said.

It worked for Kauai, and it could work elsewhere. The new challenge is to standardize the solution.

“Our goal is to drive consistency across technologies,” Kroposki stated.

Kroposki heads the UNIFI Consortium, a 60-organization-strong effort funded by DOE to standardize approaches to grid-forming inverter-based resources.

“We’re making instructions on how to connect grid-forming inverters to the grid. This includes general requirements that manufacturers can meet, specifications for operators to follow, and ways to validate everything. It’s about taking lessons learned from the Hawaiian Islands back to the mainland,” Kroposki said.

One such lesson: It helps to have everyone in the same room.

Progress in power electronics can be hampered by industry disconnects. Utilities need precise inverter models and data, but this information is proprietary. On the other end, inverter makers are not always informed of how their products fare in the field.

“With UNIFI, we’ve created a middle ground. Industry needs that back-and-forth validation of events—for utilities to see what parameters do inside the inverter and for manufacturers to understand use cases for its products,” Kroposki said.

As UNIFI finishes its final year and delivers a vast library of well-tested models, standards, and controls, the power industry also has an example to reference: Kauai was one of the first locations to embrace the new grid physics, and it turned out well for their electricity rates and reliability. Now, it is possible anywhere.

Contact [email protected] to partner with NLR for grid stability studies.

Last Updated May 28, 2025