NLR Advances Battery-Free Power for Remote Maritime Sensors and Navigation Aids

Compact Thermomagnetic Generator Delivers Continuous Electricity Using Natural Temperature Differences Between Ocean Water and Air

The key to future technologies can sometimes be found in the past. What Ravi Kishore is working to perfect, for example, has its origins in the 19th century imaginations of Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison.

“Both Tesla as well as Edison have multiple patents on this technology,” said Kishore, a senior research engineer at the National Laboratory of the Rockies (NLR), the U.S. Department of Energy’s laboratory for integrated energy research.

The two geniuses each conceived of a thermomagnetic generator that would use a change in magnetization to create an electric current. But subsequent research revealed its impracticality for large-scale production of electricity, such as the amount required for industrial applications. Fortunately, Kishore is thinking smaller.

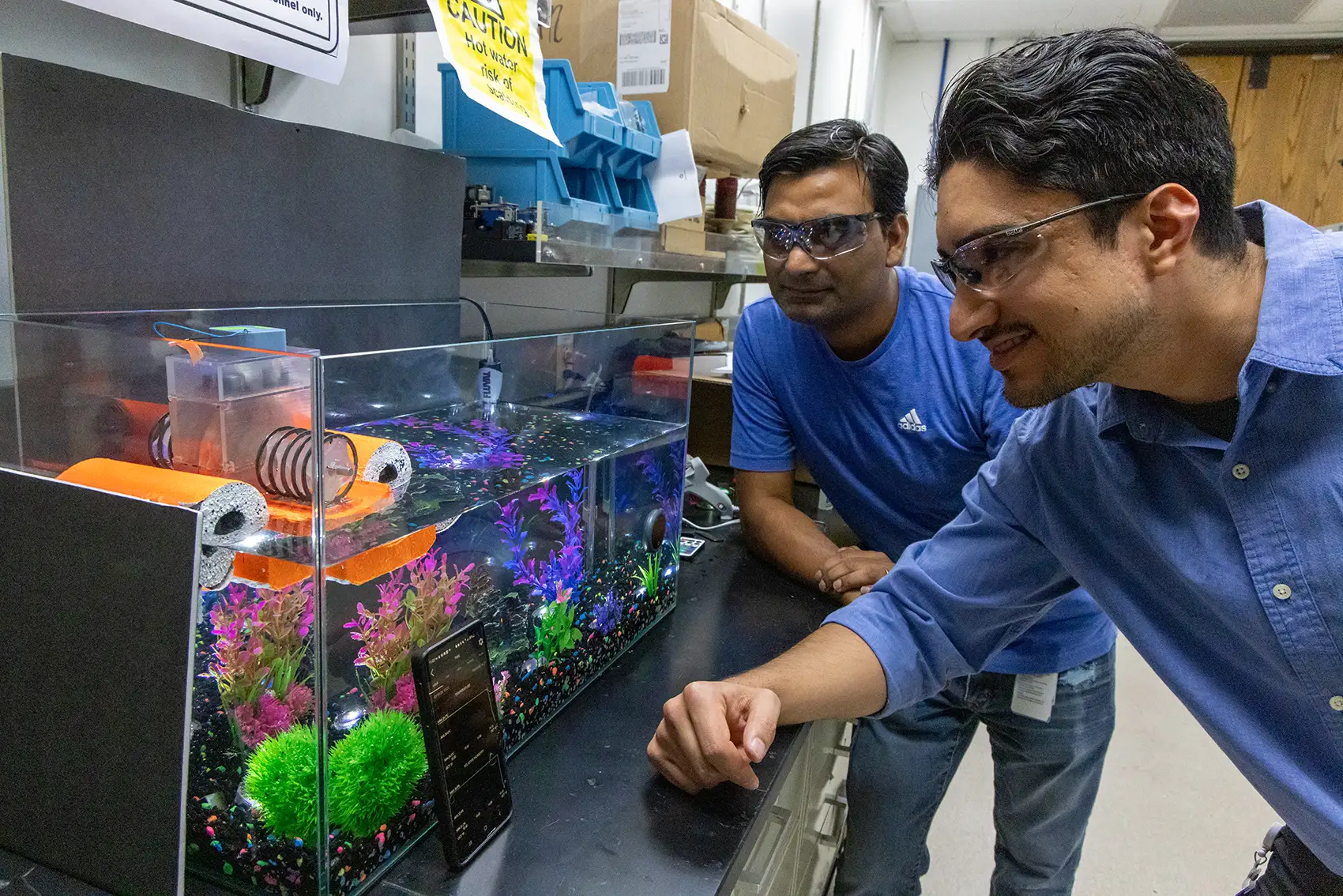

His idea is for the technology to provide just enough energy to power wireless sensors floating in the ocean. He is thinking on the scale of milliwatts rather than megawatts. To get a sense of how small this thermomagnetic generator is, Kishore tested a prototype device in a 15-gallon freshwater aquarium. The actual device will not be much larger, at about a foot long.

A thermomagnetic generator takes advantage of the difference in the temperatures in the ocean and the ambient air above the water. The NLR-developed model uses gadolinium, a rare earth element known for its magnetic properties at room temperature. The generator works by cycling a temperature across what is known as the Curie point, which is when the magnet loses its magnetism. The difference in temperatures allows gadolinium to continually shift from a magnetic to a nonmagnetic state, thereby generating electricity. The warmer temperature of the ocean and the colder temperature of the air is enough to trigger the magnetic transition.

The difference is less than 10 degrees, but the device is designed to work even when the water and air are about the same temperature. The evaporative cooling by the wind should be enough to trigger the magnetic transition.

The details are spelled out in a newly published paper, “Thermomagnetic generators for ultra-low-grade marine thermal energy harvesting,” which appears in Communications Engineering, a Nature Portfolio journal. The article was written by Kishore and two colleagues from NLR, Erick Moreno Resendiz and Tavis Peterson.

The researchers envision the thermomagnetic generators could be used to power marine sensors that wirelessly transmit their data to a monitoring station.

Achilles Karagiozis, director of the Building Technologies and Science Center at NLR, said the technology is a “prime example of how cutting-edge research is driving progress in groundbreaking energy solutions. By harnessing ultra-low-grade marine thermal gradients using the developed thermomagnetic generator, our team pushed the boundaries of energy harvesting technology and demonstrated an innovative solution to reliably power distributed maritime sensors and navigation aids used for ocean monitoring, exploration, and offshore applications.”

With the technology having passed the aquarium test and water tank test, and producing the necessary amount of power, the scientists are developing methods to protect their thermomagnetic generator from the harsh ocean environment.

“It’s not trivial making a device work in the ocean environment,” Kishore said. “It’s a very rough environment, especially when you want it to survive.”

Next, the team will conduct a field test in the ocean. Here, they will focus on the device's durability and test its efficiency in an ocean environment. The team plans to use special coatings that may prevent corrosion during the test in an effort to ensure a successful deployment.

The Department of Energy’s Water Power Technologies Office funded the research.

Last Updated May 28, 2025