NREL-Led Effort Addresses Problem of Plastic in Rivers

An avid scuba diver who also surfs and sails, Ben Maurer prefers the sights and sounds of the ocean to any other setting, so he leaves the waves and water behind reluctantly.

“I feel a lot more peace around the ocean,” said Maurer, whose home in San Diego is about a mile from Mission Bay and a couple more miles from the Pacific Ocean. “I feel a lot more excitement at the same time. It’s a really special place for me, and I’ve worked really hard in my life to stay near the water. The most miserable I’ve been is when I’ve been landlocked.”

A native of northern California who earned his doctorate in oceanography, Maurer has spent the last three and a half years with the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL), which has its main campuses in landlocked Colorado. But Maurer works from home and over the past year has crisscrossed the country, boating down major rivers to investigate the ongoing problem of waterborne plastics. He is the principal investigator of the Waterborne Plastics Assessment and Collection Technologies project, otherwise known as WaterPACT.

Financed by the Department of Energy and with collaboration from the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL), WaterPACT involves collecting samples of plastics in waterways, gathering data about the size and scope of the problem, and eventually coming up with a solution. Partners on the initial phase of the project include the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 3, Louisiana State University, University of California Riverside, Oregon State University, Portland State University, and the Moore Institute.

Maurer made repeated research trips to the four rivers involved, spending days on boats as a specially designed net sliced through the water to capture the visible and invisible plastics fouling the Mississippi, Delaware, and Columbia rivers. For the Los Angeles River, the researchers were able to work from an overpass above the urban setting. There, the pollution problem was easy to spot.

“There were three couches we counted in an hour and a half that went downstream and right into the ocean,” Maurer said.

WaterPACT Collaboration Searches for Answers

Initially, Maurer thought the information he sought about plastics in the rivers would be readily available. Some federal agency must have data listing the different types of plastics in the rivers and their concentrations. He could then take that and design solutions to the problem.

“Turns out, nobody had those data,” he said. “When we first started, I was so sure that somebody was going to email me: ‘Why don’t you just use this enormous data set that’s already there?’ And that never happened.”

WaterPACT relies on the expertise of about 30 researchers at NREL and PNNL. The researchers must determine how much plastic is flowing through the water before coming up with a solution to the problem, one that involves detecting and collecting this waste before it winds up in the ocean. The process has been laborious, involving partners at universities, subcontractors, and time-consuming work back in the lab to analyze what the nets have pulled from the rivers. WaterPACT is also relying on members of the NREL-led Bio-Optimized Technologies to keep Thermoplastics out of Landfills and the Environment (BOTTLE) consortium to better understand how the collected plastics can be recycled or upcycled.

The rivers chosen for study were picked for their different climates and weather systems, as well as for their disparate environments. The majority of the 48-mile-long Los Angeles River, for example, flows along a concrete basin, while the 1,243 miles of the Columbia River runs through wooded areas and over a series of dams. Each of the rivers is downstream of a major urban center: Los Angeles, of course, but New Orleans and Baton Rouge are along the Mississippi, Philadelphia on the Delaware, and Portland and Vancouver on the Columbia.

Maurer and his WaterPACT team are not the first to study plastics in rivers, but what the researchers have accomplished is to develop a benchmark to collect and categorize the data so that it can be comparable across any studies.

“The hope there is understanding what plastics are in these rivers,” Maurer said, “but also getting a better-tuned model of what the U.S. is contributing to global ocean emissions.”

Except for Los Angeles, crews board a boat to tow a net about three meters long through the surface of the water and at mid-depth. Merely skimming the surface would miss the floating plastics below. The net tapers to a point, allowing the capture of anything larger than about 330 microns.

WaterPACT’s river excursions have yielded a collection of waste plastics, from flip-flops to miniscule materials shed during manufacturing processes. Plastics in the rivers have been found contaminated with pesticides, pharmaceuticals, and herbicides. Some plastics contain toxic additives that Maurer said are “known carcinogens, mutagens, endocrine-disrupting chemicals.” Compounds used in the manufacture of polyurethane foam showed up in some samples. “Finding that in our samples means that we must have been next to a really strong source that is incredibly illegal,” Maurer said. “It shouldn’t be being dumped into the Delaware River, but it was.”

A single tow pulls in thousands of pieces of plastic.

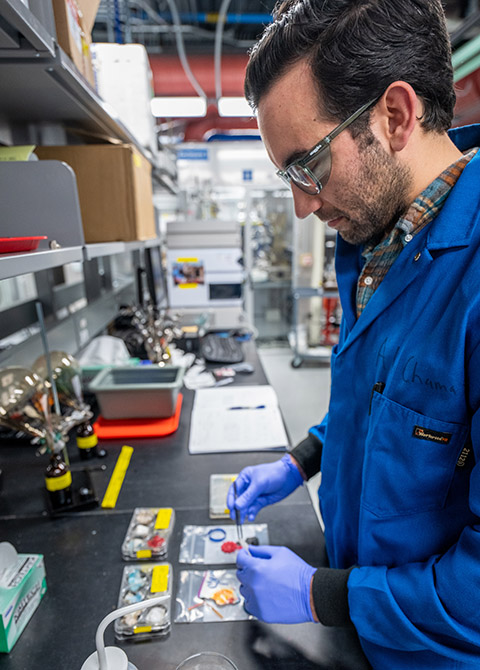

“We have to be very thorough with every piece of material that’s in these bottles that we get,” said Ali Chamas, a postdoctoral researcher at NREL who is leading the chemical analysis of what is recovered. “We check every stick, we check every leaf, just to make sure we’re not missing anything.”

Chamas, who grew up in Los Angeles, took part in collecting samples from the river there.

“We have yet to go through a sample that hasn’t had microplastics in it, which is a little disconcerting,” he said. “They are just found everywhere. In the air we breathe and our rainwater, the deepest parts of the ocean. They are incredibly pervasive.”

Rivers provide a last-chance opportunity to efficiently capture plastics before they wind up in the ocean.

Maurer Oversees Effort From San Diego

The days aboard the boat are long, beginning in the pre-dawn hours and ending after dark. Subcontractors operating the boat take the researchers to the deepest part of the river, where they drag the net back and forth. After each sampling, the net is brought onto the boat and hosed down with decontaminated water. The process is repeated until the net has been dragged four times along the surface and another four times at mid-depth. What winds up in the net is collected, stored in bottles, and catalogued. Liters of water samples are taken to capture any microplastics.

“We work with subcontractors that navigate those rivers constantly. Thank goodness we do that because rivers are pretty exciting to work in,” Maurer said. “Couches aren’t really the thing you have to worry about. Barges are, and then container ships, because you might have the right of way, but that really doesn’t matter.”

The NREL organizational chart puts Maurer’s job within the Hydropower and Water Systems Deployment Department, which is headquartered at the Flatirons Campus outside Boulder, Colorado. He said he “politely declined” the chance to relocate to Boulder, preferring instead to work remotely from his home near the ocean.

“I moved away from San Diego once,” he said. “I instantly regretted it as soon as the wheels left the ground and spent a decade almost to the month getting back here. I’m pretty deeply entrenched in San Diego now, and if I leave it will be kicking and screaming.”

Maurer received two bachelor’s degrees (philosophy, biology) and a master’s degree (engineering sciences) from the University of California, San Diego, before going on to earn his doctorate in oceanography from the Scripps Institution of Oceanography. It was after that when the newly minted postdoc jetted away to England for a position as a research associate at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics. His office was across the hall from Stephen Hawking, the theoretical physicist widely regarded as a genius.

“It was the most intimidated I’ve ever been in my life,” Maurer said. “I’ve been the dumbest guy in the room plenty of times, but I’ve never been the dumbest guy by that far.”

After two years in England, Maurer returned to America. He spent two years in Washington, D.C., at the Department of Energy as a marine systems engineer in the Wind and Waterpower Technologies Office. A five-year stint as a senior research scientist at the University of Washington followed before he returned to San Diego and began working for NREL in 2020. Even his volunteer work revolves around the water.

A scuba diver since he was 11, Maurer regularly dove in aquarium tanks in Seattle and San Diego to educate visitors about marine life. He even kept his composure during a presentation when he was bitten in the jaw by a six-foot leopard shark. He also has taught underprivileged teens in San Diego how to surf. “A lot of these kids have never seen the ocean,” he said. “They’ve grown up in San Diego but never left a five-block radius of their house.”

Hoped-For Outcome Keeps Plastic From Oceans

As much plastic as the WaterPACT project is pulling from the four rivers, Maurer sees considerably more already in the ocean.

“I see it diving. I see it surfing,” he said. “It’s really frustrating to see it diving because there’s a preserve just off La Jolla here, a marine preserve that is right next to the oceanography school that I went to, even though that’s an area that’s meant to be pristine.” For one research project, he dove 60 feet deep to study octopus. The open underground area where the octopus lived was covered with trash, giving the creatures plenty of shelter. “There would never have been that kind of an ecosystem if it weren’t for the trash people dumped out.”

The problem of trash in the ocean may never be resolved, but preventing plastics from flowing from rivers to the sea may be the outcome of WaterPACT. The data the coalition is collecting now will provide a road map for the steps to be taken, for a company to marshal the expertise provided by the research to come up with a solution to the problem of plastics in the rivers.

“I want that somebody to be us. I want it to be NREL,” Maurer said. The capabilities at the laboratory, including high-performance computing, could lead to the creation of a network of sensors that municipalities deploy but NREL operates.

“This is actually our vision, that 20 years from now can result in a 50% reduction in plastic in U.S. waterways,” he said.

Learn more about the Waterborne Plastics Assessment and Collection Technologies project.